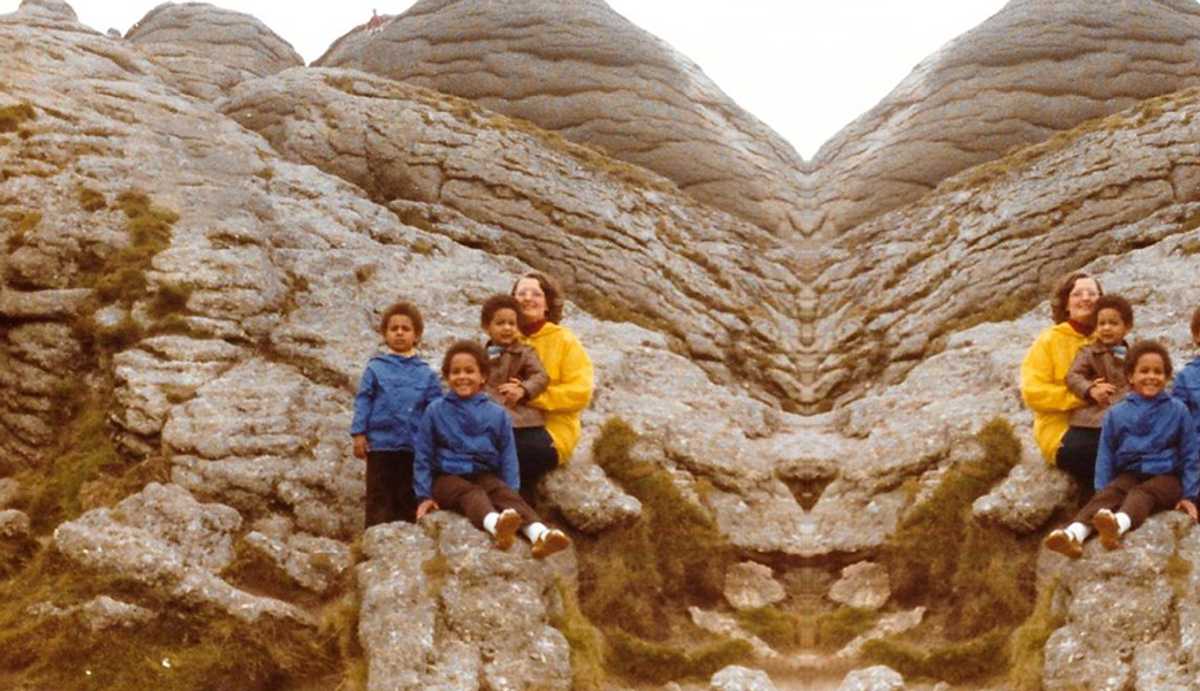

As mainstream media has begun to explore the black British experience, airing TV programmes such as Black is the New Black and Black and British: A forgotten history, ‘whitewashed’ versions of history are finally starting to be challenged and rewritten in the public consciousness. Yet emerging public narratives about being black and British still tend to be based on the assumption that black = urban. What this assumption ignores is the fact that people of colour don’t have a single, uniform experience; there are numerous, differing non-white identities in the UK. What has not been well documented thus far is the experience of people of colour in rural Britain, who have lived in the British countryside for centuries; we came as ‘servants’ from crop plantations in the former colonies, as soldiers, sailors, teachers, students and more. It is widely acknowledged that the transatlantic slave trade was kick-started in Devon, and there are numerous links between the British countryside and Africa, the Americas and Asia. Our forebears (including enslaved Africans and African American soldiers) built British rural infrastructures both directly and indirectly. BAME populations in rural areas have grown rapidly over the past twenty years as people from diverse ethnic backgrounds have moved to the countryside to work and study. There may not be as many black and Asian people in rural Britain as there are in inner cities, but these untold, unique stories are part of the national story, and they can add to our understanding of ‘race’. My own story is that I’m a black woman who has inhabited white spaces all my life. Born in Doncaster to a Ghanaian father and white English mother, I moved to Cambridgeshire and then to Paignton with my mum and siblings when my parents divorced. Devon – a place of fields, woods, reddish earth, and beaches – was familiar to me, as I’d been visiting my English grandparents there since I was little. Our house was in a valley, opposite bluebell woods. It felt like going back in time; there were no other black or brown faces around. I soon befriended the local kids; the girl next door told me her dad hadn’t wanted blacks living next to them, but we seemed OK. Most local people had never seen a black person face to face. The boys in our street racially abused us. It was 1985. When I was 19 I moved to Lyme Regis, a seaside town on the Devon/Dorset border, with my daughter. Seaside townsfolk are not generally keen on outsiders, so I’m not sure what they made of a dreadlocked black teenager (with a white baby). Everyone knew who I was. People were sometimes openly racist – I was driven out of a flat by my neighbours. I was surrounded by daily micro-aggressions: racist jokes, comments about my hair, stereotyping of black people, people using words like ‘coloured’ and ‘half-caste’, and holding the bizarre belief that anyone with brown skin standing near each other were always somehow related. The things that go on in the West Country would make urbanites shudder. Sometimes black people would have the word ‘Black’ prefixed to their names: I’ve known a Black Rob, a Black John, and a Black Dave. My daughter, in the noughties, had a friend known as Paki James. Racism in white rural spaces often goes unchallenged and unnoticed – except by those who experience it. Sometimes I thought I should leave. Black people didn’t look right against a rural backdrop. But I didn’t feel at home in urban landscapes either – in London, I felt too ‘white’ and rural. At home, I was too black and urban (people often assumed I was from London or Bristol). I have often wondered how different I would have been if I’d grown up in a black community. But the West Country is my home and I wanted my children to grow up with space and light and clean air. Black and Asian people have a right to connect with nature, although historically our relationship with the land has been denied (by white people and by ourselves). So I stayed, living as both an insider and outsider, from here but also from ‘there’, a brown face in a sea of white ones. My experience is one of many. A report called ‘Keep them in Birmingham: Challenging racism in south west England’, found “a disturbing picture of racial prejudice and discrimination directed towards ethnic minority residents.” This and other reports including ‘Racism and the Dorset Idyll’ have shown that BAME people in the South West have experienced racism ranging from inappropriate terminology to vandalism, verbal abuse and physical violence, to families having to leave their homes and businesses. The West Country’s idyllic ‘chocolate box’ image not only hides the diversity of people living here, but crucially the fact that BAME people often experience racism, isolation, and a lack of access to culturally appropriate activities and products. As marginalised people, we are marginalised further still by rural racism and deprivation. In 2001, when Jay Rayner created a ‘race map’ of Britain reflecting the rates of recorded abuses and assaults, he discovered that people in rural areas had a higher likelihood of racial attack than inner cities. In Devon and Cornwall, 1 in 16 people from the BAME community was likely to have experienced a racist incident. In London, racist incidents affected less than 1 in 50. Things have improved somewhat in recent years. Service providers have recognised that there are BAME people in the countryside, moving on from the ‘no problem here’, colour-blind approach which prevailed for some time. More people of colour are choosing to live in and visit rural areas. But it hasn’t changed enough. Chukumeka Maxwell has lived in places including Hackney and Exeter and now lives in Totnes. He came to the South West because of a relationship, and to go to university. Both his ex-partners are white, middle-class women – what he calls “my pattern” – and he has two daughters. His father was “more British than the British” – an example of how you can end up with the cultural identity of the nation rather than that of your cultural heritage. Arguably, a similar absorbing of the culture around you happens in rural places. Chukumeka says he created “a false persona” in order to survive. “I decided I’d try and be popular, and focused on how I could help others through my community development work… As I became stronger in loving myself, my blackness and my quirkiness, I didn’t need to do this so much.” Living in Devon or Cornwall, he says, you get to see how people are unsure about people of colour, and about difference more generally. “It’s part of where Empire started, our green and pleasant land, and – if you take this to its nationalist reality – ‘keep it white.’” Things can be particularly difficult for black men in rural areas, perhaps due to the ‘bad, dangerous or mad’ stereotype. Lucy* is a white woman married to a black man, and they have three sons. Moving from a multicultural city to a white rural area meant that for the first time she became exposed to hostility through being part of a black family. “I experienced for the first time how white people really viewed us as ‘outsiders’ or embraced us in a way that exoticised and ‘othered’ us. I learned to meet the hostile stares with hostile stares of my own. My husband, who was familiar with this, told me not to rise to it – but I was outraged.” Lucy’s husband would say, “You’re making it worse. Remember, it’s not you they will go for.” He didn’t have the luxury of the outrage Lucy felt. “That would be dangerous for him.” Ava Vidal is a black British woman who was born in Brixton. She went to boarding school in rural areas including Sussex and Shropshire. “Where I live now things are fine. When I was growing up, not so much. I was shielded somewhat by being at school. But when we weren’t there, it was awful. From micro-aggressions, such as people asking me what colour my blood was, to being called a wog. I was never chosen first for anything but sports teams. People mocked my parents’ accents and our food.” At school Ava would wear African prints, “but to be honest, it was mainly to annoy people. I was very militant and would not accept any racist bullying. I still had long bouts of depression because I felt like I was always fighting.” Growing up, there was nothing that represented her heritage other than the Black Panther Group she started at school, of which Ava was the only black member. Today, she feels part of “a black community of shared experiences.” For some, rural racism is a problem but isn’t as extreme as it can be elsewhere. Crystal Carter, 34, is a Black American who was born in L.A. and has lived in Exeter since 2005. She moved there “for love” and is married with one son. “I’ve made loads of friends; race isn’t a massive factor in my day-to-day existence. People expect to see different ethnicities here because of the hospital and the university; it’s not a big deal.” Crystal has witnessed and experienced some racism, and has heard of others, particularly Muslims, who have received “more direct racial aggression.” While she doesn’t consider this acceptable, Crystal is conscious that it pales in comparison to the kind of racial stress she endured in the USA. Some of Crystal’s happy memories of Exeter include working on the ‘Telling our Stories, Finding our Roots’ project, and participating in protests against the EDL and Trump’s Muslim ban: “These stand out more than the racist incidents.” Crystal often wears African fabric headwraps, as it makes her feel connected to the African diaspora and because “black women worldwide have been doing this for centuries.” She feels connected to both the black American community and to Exeter’s black and activist community. Yet, when she worked in smaller towns in Devon, the experience was very different. “I felt the pressure of being the only black person, or the first black person someone had met, or having to look at golliwogs on display. It might not have been overt racism, but I didn’t want to be on duty all the time. I appreciate my blackness but if I’m out for a pint I don’t want to have to deal with the fact that someone is too much of an idiot to realise that blackface and an afro or dreadlocked wig are never, ever necessary.” Geography certainly plays a part, and experiences can differ between cities, towns, and villages. Dr. Anjana Khatwa Ford, 42, is a British Asian Earth Scientist who was born and grew up in Slough and has lived in the United States and London. She now lives in a Dorset village with her partner and three children and has found it harder to fit in there than where she lived previously. “I have recently moved to Corfe Mullen and I have found it hard to fit in as the community isn’t as diverse as Dorchester. Most recently, I have been saddened and shocked by incidents of abusive racist language directed at BAME pupils at my eldest stepson’s school.” Anjana, whose family are from Kenya with Rajasthani Indian ancestry, moved to Dorset from the United States for work. She tells me, “I was shocked by how beautiful it was. Anyone working in earth sciences dreams about living here! I was immediately connected to the story of the rocks, fossils and dynamic coastline.” But she was also shocked by local attitudes. “When I walked into village pubs, all eyes would turn on me. There’d be a hushed silence. At work, people went to great lengths to tell me how much they loved curry or would describe someone they know that was from the same cultural heritage as me. Few people could pronounce my name.” The worst racism she experienced was in Dorchester, walking behind a nun, who was also Asian. “A young man yelled out of a car window ‘go back to your own fucking country!’ What shocked me at first was that he had spoken like this to a nun! Later on, I felt angry that all the work she and I did for our community seemingly did not matter and that it was the colour of our skin that did the talking. Another time, after Brexit, a man came up to me in a shop and kicked the shopping basket in my hand. Although he didn’t say anything racist, I felt I had been specifically targeted.” After a few years of living in Dorchester, however, she made friends and being BAME in a white area became less important. Anjana has carved out an identity for herself by becoming “the champion for diversity in the field I work in.” Christy Ku, 22, is a Chinese videographer and writer who lives in London. For her, living in predominantly white parts of Britain such as Southampton and Exeter had a lasting impact; being subject to racism was part of her daily life from a young age. At school, she was one of three East Asian people and the only girl. “It got to the point where I knew if I left the house, I would receive abuse. If I was seen by them, they had to go out of their way to hurt me. Once, at school, an older boy was on the phone. He noticed me walking past, spat out a slur mid-conversation and returned to his call.” It was mostly schoolchildren who attacked her. Home was not a safe space, either. Christy lived in a rough neighbourhood and her house was frequently stoned or egged by neighbours, particularly on Halloween, until the family moved. Christy was quiet and withdrawn. “I didn’t know how to talk to people who looked different to me. I looked alien and felt uncomfortable.” She only began to embrace her identity in the last year of school. “I wore a qipao to prom. In sixth form, I let my hair grow down to my waist.” (She’d previously kept it short as she hated her thick Asian hair). Christy has never felt part of a Chinese community either. “I’ve spent most of my life in England so I have little knowledge of my heritage. There is great shame in the community about being too ‘Westernized’ or ‘not being Chinese enough.’ I’ve given up searching for a community. I’ll know it when I find it.” Christy has struggled with social anxiety and a fear of going outside, which continues until today. Overt racism occurs less these days, and she has “found ways of handling it”. She is aware that the threat is real, but also feels that it is not enough to simply be around other people of colour. “You can’t generalise all ‘non-white experiences’, because so many experiences are specific and the product of coming from a certain heritage.’ The same can be said of the specific experiences people of colour have in rural places, and although these experiences vary enormously and are affected by factors such as gender, socio-economic background and geography, there are commonalities. Most of us experience or witness racism, which often stems from ignorance and a lack of contact with non-white communities on a regular basis. What also stands out is the isolation felt by many, caused by a lack of people, food and activities that reflect our heritage. Creating a sense of identity when you look different to nearly everyone around you is challenging, particularly for young people. Most of us have attempted to ‘blend in’ with our largely white community in some way, either by adopting different personas, choosing white partners (as many people I know have done, although this is often for practical reasons) or accepting racist behaviour. So how can inclusivity in white rural spaces be improved? Having more black and Asian move to these areas would certainly help, but this alone is not enough. Chukumeka suggests that it is not always about the colour of the person but their attitude. “Community is more than black people, it’s everybody. It’s about what binds us as human beings in relation to nature rather than stereotypes/political constructions of race or gender.” Structures and communities need to be built, ‘ethnic’ foods and hair products need to be made available, arts and cultural events would help bring communities together. Ava believes that more people of colour moving in would make people who live there “less fearful of the unknown,” and points to the fact that black people in cities are not as vulnerable or exposed. “When the tide turns they have a place to hide. We do not.” Our experience is certainly one that our fellow city-dwellers might struggle to understand; us black and brown rural folk are highly visible, yet also invisible when it comes to having our needs met or our voices heard. For me, life in white spaces has been challenging. I have had to work through deeply internalised racism to reach a place where I embrace my black, rural identity. There are many discussions around the experience of black, brown and immigrant communities in the UK, but in the countryside, it might only be one family of colour or a few individuals in the entire town. I’m conscious, as others are, of the pressure of having to ‘represent’ all black people, and that mine is often the only brown face when I walk into a room. Yet I am hopeful things will change and that rural landscapes will become more multicultural and inclusive. People of colour have as much right to connect with the countryside as we do with urban spaces, and we shouldn’t be afraid of doing so. *name has been changed Photograph courtesy of the writer

Where are you really from?: The hidden lives of PoC in rural Britain

On the right to the countryside and how the focus on people of colour living in cities often means that those living in rural areas don’t get the support that they need and have their experiences overlooked…