Last Monday, the European Union signed a deal that allows its member states to deport any number of rejected Afghan asylum seekers. Leaked memos revealed that the aid packages to Afghanistan dished out ever so generously at last week’s donors conference in Brussels have been made ‘’migration sensitive’’; their renewal depends on the Afghan government’s willingness to readmit an unlimited number of Afghan asylum seekers from Europe. The very conditions of conflict and economic inertia that produce displacement in the first place and make rehabilitating these refugees impossible thus also left the aid-dependent and embattled Afghan government with no choice but to pretend to the contrary. As such, the deal is emblematic of wider post-9/11 European policy shift: away from pledges of protection under the Refugee Convention of 1951, and towards externalizing ‘’the refugee problem’’ through a combination of intensified border controls and containment, preferably in ‘’the region’’, but alternatively at Europe’s fringes. The European Union pays three billion euros to Turkey to patrol fortress Europe and 198 million to cover the frappos of inefficient government and INGO workers tasked with making the open-air and open-gate prisons of Greece less embarrassingly undignified. Just as we downplay worsening conditions in Jordanian and Lebanese refugee camps for Syrian and Palestinian refugees, the EU memo suggests that ‘’dialogue with Iran and Pakistan’’ can redeem the severe hostility faced by Afghan refugees in these countries. The memo wishes away the well-publicized restrictions Afghan refugees face in Iran, where most can’t get a driver’s license, attend university or use medical insurance, and where they reportedly risk being forcibly recruited into Iranian pro-Assad forces. It conveniently ignores the humanitarian crisis that is developing in Afghanistan’s East as a result of Pakistan’s decision to order its 3 million Afghan refugees to leave earlier this year. Meanwhile, the category of ‘’Internally Displaced Person’’ ensures that those internally displaced remain internally contained in conflict-torn countries disingenuously declared ‘’war-free’’ and safe. Bribes, blackmail and strategic categorization practices combine to diminish European responsibility under international conventions, replacing solutions with legal and ‘’humanitarian’’ ways to squeeze the problem elsewhere. An hour before news of the deal reaches me, I receive a bundle of postcards from Samos. Images of the Greek island’s idyllic beaches and quaint towns contrast sharply with the cramped and barbed-wire crowned ‘’reception center’’ in which the postcards’ authors live. They are a bunch of Afghan teenagers I had the privilege to teach when I volunteered in the camp. The postcards, I know, are an assignment their other volunteer teacher has given them, but I am moved by their messages nonetheless, and struck with that most typical of White Saviour realizations that ‘’they stayed behind’’ when I returned to my university education. The seemingly unshakeable enthusiasm for education manifest in their voluntary and consistent attendance should be besides the point here, as are the absolutely gruesome, nightmarish encounters and journeys some of them have lost relatives to; we all at least feign a belief in every child’s right to education, and a quick survey of European states’ Foreign Ministry websites (never mind expert agreement, media coverage of recent Taliban onslaughts, and your own qualms about a holiday in Helmand) shows that Afghanistan is still firmly in the no-go bin of travel advice. Yet I bring up these boys and girls to drive home the urgency and feasibility of finding a genuine solution to their displacement in the world and their de-socialization in camps, by which I mean they are reduced to ‘’bare life’’ without proper access to formal education or employment for an indefinite period of time. Either we can extend our citizenship privileges and education systems to these teenagers and adults – who complained vehemently about a timetable clash between informal Greek and German lessons – or we can condemn them to a life of precarity and unsafety in Afghanistan or its neighbouring countries. ‘’There is not even this little place for us,’’ repeated an especially disillusioned Hazara man one evening, keeping his hands six inches apart to symbolize the safe space denied to his Afghan minority (despised and haunted by the Taliban, who had allegedly murdered ten out of the man’s fourteen relatives). If European leaders decide to spend less time and money devising blackmail schemes and inventing identities that detract from the status of refugee and dodge the responsibilities it warrants, we can prove him wrong. Practicing adjectives, one of my former pupils put it more simply:

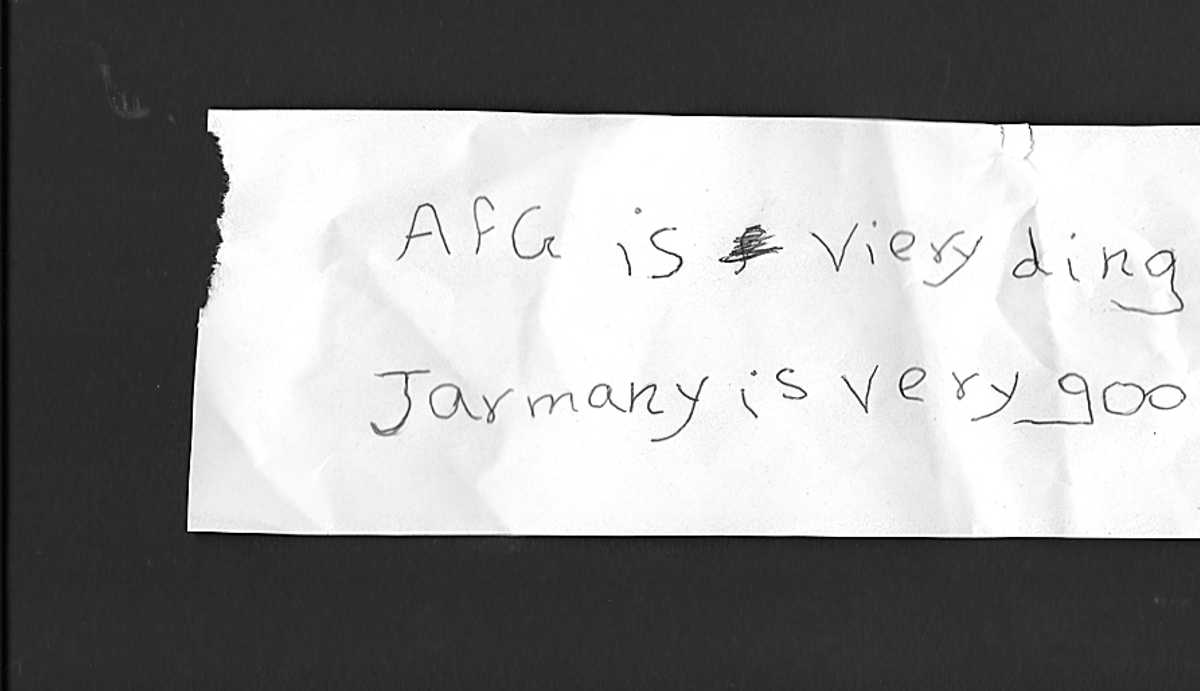

AFG is viery dinger. Jarmany is very good.

Let’s not pretend otherwise.

The image used is a replication of the original note.