London-based mixed media artist Merissa Hylton is a woman of many talents. A sculptor, painter, potter and textile artist, she feels most at home working in clay. Hylton has Amniotic Band Syndrome, which means she has no fingers on one hand. It is with her hands that she explores her identities as a Black disabled woman, feeling and manipulating the malleable texture of earth mixed with water.

Since leaving her career in corporate design architecture to become an artist full-time, Hylton has exhibited her artwork throughout London and has been a featured speaker for Late at Tate Britain. In 2017 she founded Black British Visual Artists, a platform for Black artists in the UK to network, exhibit and share their work, that also provides education and mentoring for young & emerging artists.

Recently, she moved her work from home to her very first studio space in London. Alyssa Jaffer chats with Hylton about lineage, lockdown and the art of affirmation.

The conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

Alyssa Jaffer: Congratulations on your new studio! How does it feel to have your own space to create?

Merissa Hylton: It’s so freeing. My creativity has definitely been limited, because I am drawn to working on a large scale. Working from home, I can’t create really massive pieces.

AJ: What was your life like in a pre-coronavirus world?

MH: I’m a homebody, so for me, lockdown wasn’t really an issue. The only thing that I really missed was the art exhibitions, seeing my art crew. You take freedom and accessibility to things for granted. Then it’s taken away, and it makes you realise what you had before.

AJ: You use motifs from your many identities in your work – symbols of African cultures and traditions in your paintings, for example. How does your ancestry play a part in your art?

MH: I’ve been interested in my own family history and genealogy. When I started putting together the stories of my ancestors, I was fortunate to have great-grandparents that were still alive. Learning those stories, I felt the need to trace it back further, to understand more about the African side, and how that influenced the Jamaican side of my family.

For the most recent piece I did, the “Sankofa” sculpture, I learned about the West African Adinkra symbols. The Sankofa symbol stood out to me because it translates to: ‘go back and fetch it.’ The meaning is to look back at your history and learn from it, and it has resonated with me a lot.

AJ: Your sculpture, “I am Here – Acceptance” depicts your hand and Amniotic Band Syndrome. Tell me about that piece and what it was like to bring it into the world.

MH: It came about as a result of a unit I’m studying: Inclusive Teaching Practices, covering disability, race, religion and gender. It really made me look at my own work and myself. Previously, I hadn’t considered myself as disabled. Apart from the fact that I don’t have fingers on my right hand, I’m actually ambidextrous. But I had to explore the fact that throughout my life that I’ve had to adapt so many things, in order to just to get through. I started looking into the representation of disabled artists – particularly disabled Black artists – and their visibility in the arts. You can’t be what you can’t see.

That’s the most personal piece I’ve produced because it left me quite vulnerable. It made me reassess the way I look at my hand and how I feel about it, and that it’s taken me the majority of my life to accept it. So that was quite a revelation for me.

AJ: How does it feel, now that it’s out there?

MH: I love it. It’s been really freeing. Now that it’s out there, it feels like I’ve taken a breath. It’s a sigh of relief.

AJ: It’s a perfect example of art as a form of creative therapy, a notion you’re a vocal and passionate advocate for. Especially now, there’s a desperate need for artistic expression as a type of therapy.

Systemic racism has been hyper-visible this year in a particularly traumatising way for those who have long experienced it. Do you have anything to say about 2020 as a reckoning moment for people who are only now confronting systemic racism?

MH: I feel very strongly about sharing trauma porn. I don’t watch any of the videos. I don’t look at the pictures. I don’t feel that constantly seeing Black people being killed benefits anyone. It’s almost like, the more you share it, the more you become desensitised to it.

It’s not something that’s ever going to be right and it’s not something that should ever be the norm. This year has really shown the true colours of people, organisations and countries. In America, descendants of enslaved people still live with the descendants of the masters. Whereas in the UK, people are so removed from the legacy of slavery and the racism as a result of it.

I personally don’t think that it’s ever going to go away, because it’s in the fabric of these countries. It doesn’t matter what you do. You can be compliant, you can follow orders and you’re still going to get killed if you’re Black or brown.

AJ: Some of your artwork delves into that struggle against systemic racism, the pain but also the beauty. Have you made any pieces to channel that emotion?

MH: I created a piece called “Affirmations” that was exhibited at the Black British Visual Artists exhibition last year. It was a response to the Windrush Scandal and the policing of Black bodies, Black women and their hair.

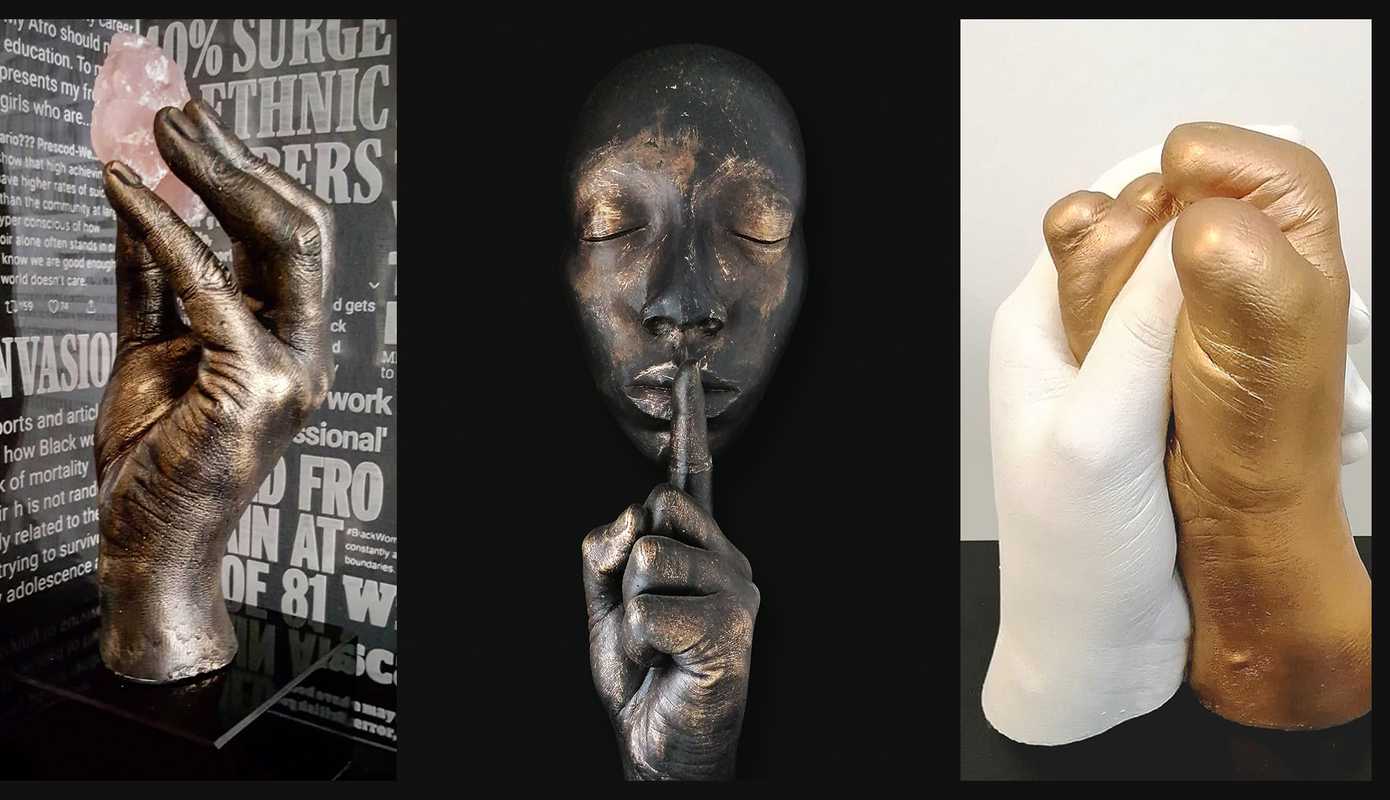

The sculpture is a hand holding a rose quartz: a crystal for protection and self-love. The hand is surrounded by negative news headlines. That piece was created for myself and my response to how I deal, which is with affirmations: to constantly remind myself that I am worthy, I am important, I am blessed, I am beautiful. Even though I’m constantly bombarded with this negativity, I have the power as to whether I take that in.

That was another personal piece.

AJ: That personal touch in your pieces is, to me, what makes them so captivating– like your award-winning sculpture, “Be Still & Know,” exhibited at the Bute Street Arts Festival last year. The sculpture, a cast of a Black woman with closed eyes and a finger to her lips, evokes an invitation to pause and reflect on what’s within.

MH: The pieces that have the most impact come from a very personal and spiritual place. I don’t ever create work because something is trending – it’s always a very personal response.

See more of Merissa Hylton’s work: