Marwa al-Sabouni is a Syrian architect and the author of The Battle for Home (2016). In the book, Marwa charts how recent architectural and urban planning practices contributed to the collapse of the social fabric in Syria. In the face of massive reconstruction efforts that have already begun, Marwa also promotes a craft-based approach to construction that embraces the wisdom of earlier practices and designs, and the social interactions that they fostered. Skin Deep contributor Courtney Yusuf caught up with Marwa to discuss her work, inclusive city building and the role architects play in building the future.

***

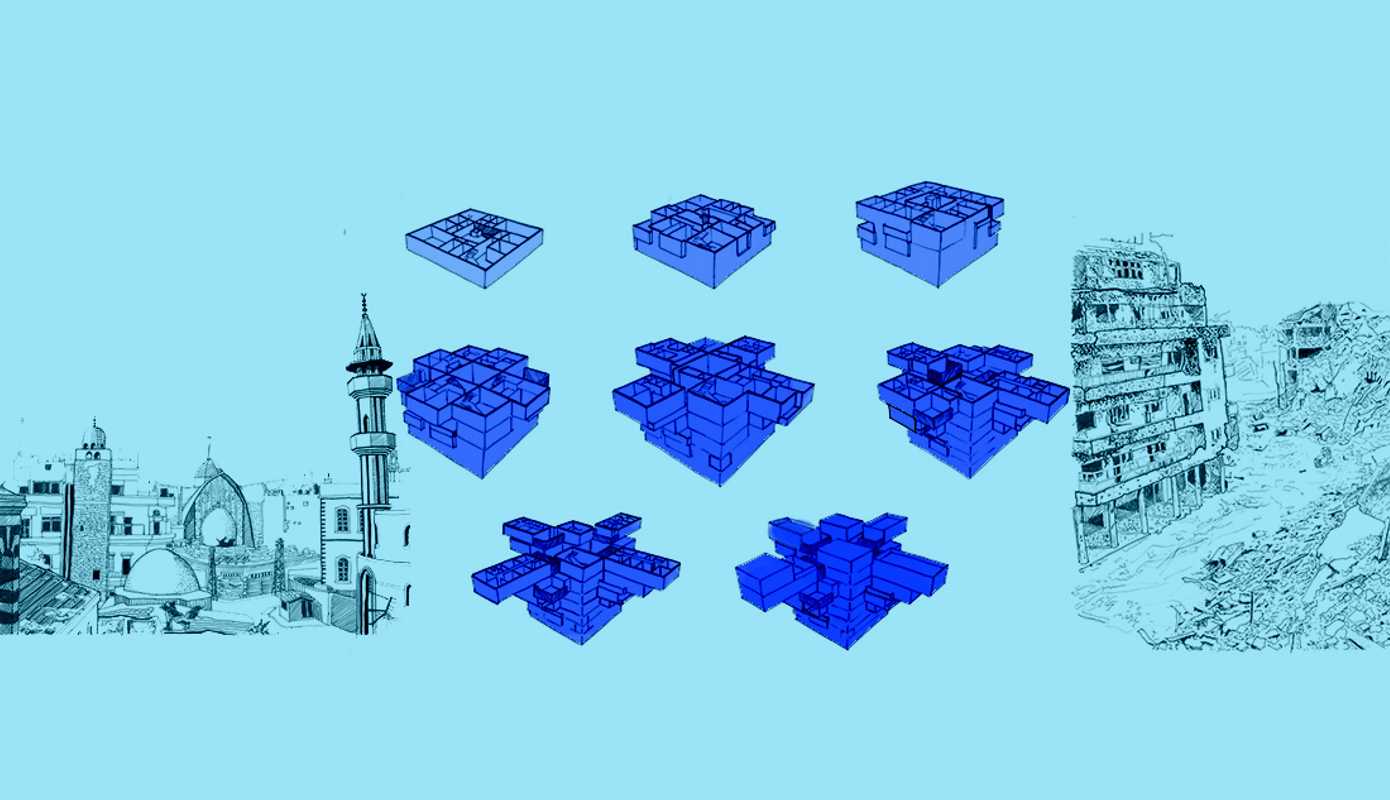

Courtney Yusuf: Where is home for you right now? Marwa al-Sabouni: Obviously it’s where I live, where I have chosen to be based and never leave, so it’s here in Homs, in Syria. It’s not just the apartment but rather the city and the neighbourhood, the faces you see everyday and the location where you have your roots. CY: Do you think you can have more than one home? MS: I think that ultimately there is just one home, not several homes. I think that when someone talks about having several homes, they are going through a searching process or an experimental phase. After all, home is the place where you feel settled and settlement is the opposite of moving. Language is very important for a home, alongside the people you encounter and understand, and the physical place as well – whether it’s the nature, the topography, the architecture, or the configuration of the built surroundings. These all lead to the most important thing: belonging. When you know a place, know how to navigate it, and feel safe there, you become emotionally attached. CY: Do you think it is possible to create a new home? With so many refugees and migrants in Europe at the moment, is it possible to build a city in an inclusive way that helps people feel a sense of home? MS: Every case has its exceptions but in general I don’t think that the first generation can make another place home. I believe that those migrants who go and seek another place to live or work have this sacrifice in mind: It’s not for us but for our children or grandchildren. They sacrifice their own belonging, their own feeling of home, for the sake of those who would come afterwards. When they emigrate it’s for practical reasons, leaving unsafe or dead-end situations, and not to realise a dream of resettlement. They always have their eyes back on the home they can’t return to. Their children will sense this state of conflict and some of them develop this sense of detachment to the place that their parents chose. I think it takes generations to feel that you belong. Look at countries that are made of immigrants, like the United States. Notice how many people are focused on their ancestors and where they originally came from. I think it’s human instinct. CY: If our aim is then to foster a long-term sense of belonging in future generations of new arrivals, are there any steps a city can take to promote a sense of home? MS: Yes, surely. I’m reminded of a poem by Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish: In Damascus a stranger sleeps on his shadow standing, like a minaret in the bed of eternity/ doesn’t long for anyone or anywhere. It’s a metaphor for how, before the war, strangers and foreigners felt an instant sense of belonging and of being welcome in Damascus. I feel that this welcoming factor was the outcome of how the city was built and how it perpetuated certain patterns in the daily relationships among its people. It was built surrounded by abundant natural resources which, integrated with the architecture, created a sense of generosity and avoided conflict. I’m speaking mostly about the older parts of the city although you still find similar features and characteristics in newer neighbourhoods. I discuss this in the Battle for Home; how in housing, or in the marketplace, or in the spiritual or religious buildings, these built patterns – the scale of the buildings, their shape and forms, their use of materials, even the use of shadow or light or the existence of water fountains – played a role in creating a pleasant place to visit based upon sharing abundance and creating a sense of relaxation and welcoming. Of course it was no utopia, but these aspects allowed people to live side by side and to welcome strangers. CY: Do you think it’s possible for European cities to apply some of the principles that you’ve just talked about in helping to integrate new arrivals into the cities? MS: Only if they change their policies. Most Western policies are built on a business relationship – they want immigrants for their labour and only open the doors to those people because they want them for a specific function. This is not like in my country where in the Ottoman era they were given space to create their own production, to practice their own rituals and social habits, as well as the rights to own property. Then, after this production, came trade. I mean, trade is the main characteristic of a city – you don’t have a city without trade. With trade comes negotiation, and having those negotiations and relationships creates a sense of acceptance in one part and a sense of belonging in the other. When two parts depend on each other their existence is no longer a neighbouring existence but an interrelated existence. Now our modern cities are built on services more and more… that’s a big issue. CY: If trade is such a key component in creating an interrelated existence, how do you think the rise of automation will affect the city as a place to live? MS: For me, this will be the beginning of an end for the city. By making the city a machine like Le Corbusier dreamt after World War II, you are removing the human factor – its basic nerve. But I’m sure people will remain and they will not just stand still and be pushed into the periphery of a city in service to a robot-controlling elite. CY: How does the social interaction generated by architecture differ to that of social media? MS: It’s a real encounter. In a narrow street I will see your face. I will have to pass by you and say hi. However, I compare streets like this to the streets I have seen in Berlin. When I visited there, I was horrified by the widths of the street. It’s so enormous that you don’t see anybody. In these vast squares that were meant to hold massive crowds, you feel lonely and vulnerable because you don’t see anybody, even though it’s filled. I’ve spent very little time in Berlin but I didn’t like it at all and thought that it was a very cruel place. I called it Robot-land because it was so robotic and military-made; the facades were all rigid, grey, ordered, big, pushing you away – the opposite of a welcoming city. CY: That’s a shame – there are now so many Syrians in Berlin. You’ve spoken before about engagement with craft being an important way for people to feel connected to a place. Is this approach just specific to Syria or can it apply to other places? MS: Yes I think it can be applied anywhere. It can be done in any city that has produced building patterns based on local production. Older architectural practices used a mason, a blacksmith, a carpenter, a plaster worker, all of whom had a role in constructing the building. It was not only the architect who assembled the different elements but also these experts who created the necessary character for a place where the elements were in harmony with each other. But what is also important in craft is the discipline: the time that it consumes, the knowledge it demands, and the hierarchy that it is based on. Before, there would also be a master of the craft who would have the greatest expertise, the best work ethic, and a good social reputation. If I were not happy with the product that you gave me and we reached a dead-end in our conversation, we would go to the master of the craft to resolve it, like a judge of its own vocation. This social hierarchy guaranteed the good quality of the product. CY: How can we put forward this argument in favour of craft and both its quality and its role in society in the face of automation and market forces pushing people in the other direction? MS: It’s not an easy one. Businessmen and companies don’t want to lose – they want to make a profit. Ultimately the war in my country is the most convincing argument. When people are pushed into a corner and have no thread to attach them to a place – they don’t like their homes, don’t care about their built environment, and are alienated from each other and the city – it becomes very easy to destroy. What kind of short-sighted strategy would those companies have if they were to repeat the same building patterns again? CY: Is it possible for an architect to make positive interventions in a city without relying on market forces? Are they solely dependant on commissions and the market? MS: In a very large part yes, because the decision makers (the city authorities) have made the decision to be partners with the developers. But I think you can break this monopoly by convincing the authorities of the importance of their decisions. In the end, as the Syrian war proves, bad decisions mean that everybody loses so why not be wise from the beginning? Businessmen are businessmen and will always care about profit. As for the architects…most of us have been in the service of the developers, with the aim of promoting ourselves. We want to be stars and once you are taken by this ego to make a project that will make headlines, you are letting go of your responsibility. We must be willing to work on a smaller scale, making more responsible choices, even if that means using a lower voice. It’s easier to convince ordinary people of what’s good for them than it is to convince wealthy businessmen who are interested in profit. It’s much easier to reason with people who have no money! But this doesn’t mean that we have to choose only one side; we have to work on both fronts, the bottom-up, small scale, individual initiatives, as well putting these arguments in the face of the authorities and the developers. CY: The West and western architecture is the axis to which so much culture and architecture is compared to – do you think this will remain the same? MS: This is currently the case in my country and it is based on colonial history and an inferiority complex. People here either despise the West altogether and don’t want anything to do with it or they worship the West and measure everything against it. Even now when the government promises something, they promise a constitution of a Western standard or they promise a reconstruction project that the West will admire. We don’t care, we shouldn’t care – we should measure everything on what is right for the people and what is right for the situation. You benefit from the experiences of others, including the West, but it shouldn’t come from a place of inferiority. We should let go of this colonial history now. Once people do one thing for themselves according to their standards, according to what suits them, and see the results, things will instantly shift. But as long as we continue in this way, we will remain in this cycle of continuous failure, always coveting what the other has. CY: What’s next for you, what are you looking forward to? MS: (Laughs) I don’t know, this war taught me a very good lesson – don’t plan too far ahead because you never know what’s coming. But this doesn’t mean that I don’t work as hard as I can. So right now I’m writing for the next book and we’ve got the work of our studio. We’re continuing to use the potential of the moment but we are not planning so far ahead. You can buy Marwa’s latest book The Battle For Home: The Memoir of a Syrian Architect here.