We caught up with Cassie Quarless and Usayd Younis, the filmmakers behind the documentary Generation Revolution, a film that provides a snapshot into the lives of a new generation of black and brown activists who are working to change the social and political landscape in London and beyond. Since the premier of the film at Sheffield Doc/Fest last year, it has been screened in cinemas across the UK, and has toured the United States, Brazil & Argentina. Ahead of the official online release of the film today, we chatted with the directors about showing the difficulties and struggles of activism on screen, creating cross continental solidarity movements, and imagining and creating new systems worth fighting for.

*

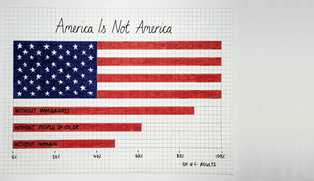

Skin Deep: What was the reaction to the film in the UK? Usayd Younis: The UK response was overwhelmingly positive, especially from young people of colour. We had the odd white person saying ‘why are white people not being represented?’ but overall there was a shared sense of ‘we needed this, this speaks to me, and I can see myself in the characters.’ It was nice to bear witness to that. SD: And outside of the UK? Cassie Quarless: I think the most amazing thing was the recognition of the experiences of these activists. Speaking to people of colour in America, Brazil, Argentina etc, a lot of them didn’t know that this type of thing was going on here: police brutality, gentrification, homelessness. People recognised that these things happened in their local context in St Louis or the Bay Area, but knowing that their brothers and sisters in the UK are going through a lot of the same things was really powerful. These are activists who are organising in similar but different ways – in relation to their local context. SD: Did you intend to create a film that might engage in the building of a cross continental solidarity movement? CQ: The genesis of the film was three years ago. Back then the media were talking about Black Lives Matter and activists in America, but no one was really talking about what was going on here. We were troubled by the fascination of the UK media with talking about race in another context, but a denial of race and racism here. SD: This country has a long history of doing that. CQ: Exactly. So we wanted to reshift the balance. Why don’t we talk about what’s going at home? Would that be more uncomfortable for you? Our motivations for making the film also came from a need to talk to our peers, and for them to use the film as a tool. We wanted young black and brown people to see that those on screen didn’t look very different to them, they had similar experiences, and shared some of the same troubles. These people that we follow on screen decided they couldn’t take the injustices anymore and were going to do something about it. We wanted people to see that and say: if these people can do it, why can’t I? SD: It’s interesting to be able to interview you now, a year after you made the film, since the disbandment of the London Black Revs, and the emergence of the Black Lives Matter movement in the UK, which you allude to towards the end of the film. What was the reaction to the film from the activists that you made it with? UY: It was mixed. This film attempts to show a realistic impression of what it’s like to be an activist. It’s not glamorous or easy, there are difficulties and internal struggles. I have to say that audiences have thanked us specifically for including the more uncomfortable side of activism. The expectation of an ‘activist film’ is something that’s very dogmatic. Actually, we don’t think this film tells you what to do. It’s a film that wants you to ask questions and to challenge not just the external systems of oppression, but also how we internalise them within our own structures. SD: In the way the film was cut it seemed like you were encouraging the audience to compare the methods and outcomes of the two groups: London Black Revs and R Revolution. Was this intentional? CQ: The two groups were interesting to us because they were both intersectional feminist organisations. Though they were black and brown activists, they also felt it was important to highlight the fact that you can’t isolate race from issues of gender, class, or sexuality. That was the starting point. But we also recognised that they had different methodologies. We didn’t want Generation Revolution to posit them against each other or say that one was doing the ‘right’ thing. And we also didn’t want to be prescriptive in the kind of activism that we portrayed. UY: We wanted to do away with the image of activists as people with endless drive and passion. It’s actually really exhausting and tiring, and people doubt themselves constantly. Spending so much time with these people, one thing that did become absolutely clear was that everybody had a deep sense of a duty to make a difference, to make a change in the world. I think this comes across particularly in Tay, the youngest guy in the film. Often they can’t describe their motivation because it’s something that is so personal, so deep – it’s the purpose of life. CQ: These are five people that we followed on screen, but you have to think that there are 1000s of other Londoners, Britons, and young people in the world who are talking and organising in similar ways. It’s easy to be despondent when reading the news and seeing all the shit everywhere, but it’s also important to take a step back and see people who are thinking along the same lines as you. It allows you to reflect: maybe we will be alright. I think we can also make a comment about filmmaking as a form of activism, and our position as directors. We want to encourage people of colour to make radical films that challenge the status quo. Filmmaking is a privileged space. This is why our histories as black folks are so much more developed in other areas than in film, because film is so capital intensive. If you want to make a good film you need much more money than if you want to make a good record or painting. Like many other filmmakers of our generation we’ve got important and interesting things to say and we should have access to the same resources that our white counterparts do, so that we’re able to tell these stories in a way that benefits our communities. UY: This film doesn’t centralise any white characters, which is something that is not done enough. To have a cast of black and brown characters that represent themselves, who are complex, multidimensional human beings with flaws, and who are also activists that care about the world is so rare. It might not seem that revolutionary or radical, but for us it was a really important part of the film. SD: We want you to talk about the visualisation of violence against black and brown bodies. Often it feels like we are being saturated with images of violence against black and brown communities to the point where we aren’t even given the space we need to imagine anything different. What role does your film play in this visualisation of violence? UY: People misunderstand what violence means sometimes. I think the idea that brutal violence – people being beaten, hit, shot and killed – is the entirety of violence is a gross misunderstanding of the term. If we’re truly talking about dismantling systems of violence we have to understand first what it is, how it’s enacted on ourselves as individuals and our bodies, but also on our communities both historically and today. Some of the most brutal violence is about restricting movement or preventing people from experiencing freedoms. People often talk to us about the scene where Josh is confronting the police officer on Westminster Bridge, saying we could never do that because the police in our country would be extremely violent towards us. But when I see that scene I feel violence all around him. I see him situated at a site of violence. Even in terms of police brutality, you cannot have individuals or a system that acts in such a violent way without it being surrounded by an infrastructure of violence. We always have to bear in mind that the powers that be have had these conversations, they’ve set the definitions. Property = value = life. You can defile and be violent towards property. Why are we not then reimagining what is sentient, what matters, and what gives purpose and meaning to the world? SD: We really appreciated the focus on the aspect of education, within and outside of the organisation. We have to know the system in order to dismantle the system and create new systems. Do you see your film as an educative tool in understanding activism and organizing in London? And what would these new systems that we’re trying to create look like to you? CQ: Wow. That’s a big question. UY: We’re trying to play a small part in a very big but necessary change that needs to happen. I can’t claim to have a solution to a better world, but I can say that addressing imbalance in its many guises is the first step. CQ: Like the people in our film, we value the destruction of the systems of white supremacy, capitalism, patriarchy and heteronormativity. But what that looks like? I don’t know myself, but I also don’t know if anyone can necessarily tell you what a world beyond these value systems might look like. Every single person in the world has been taught under and integrated into these systems. How might we interact with each other when these systems are brought down? It’s unpredictable. I don’t know at what pace or how far we’re going to go, but it’s through the tireless work of a lot of activists, like the ones we were able to film, that makes it seem like we’re going somewhere. And that has to be encouraging. Generation Revolution is now available to order online as a DVD or digital download.