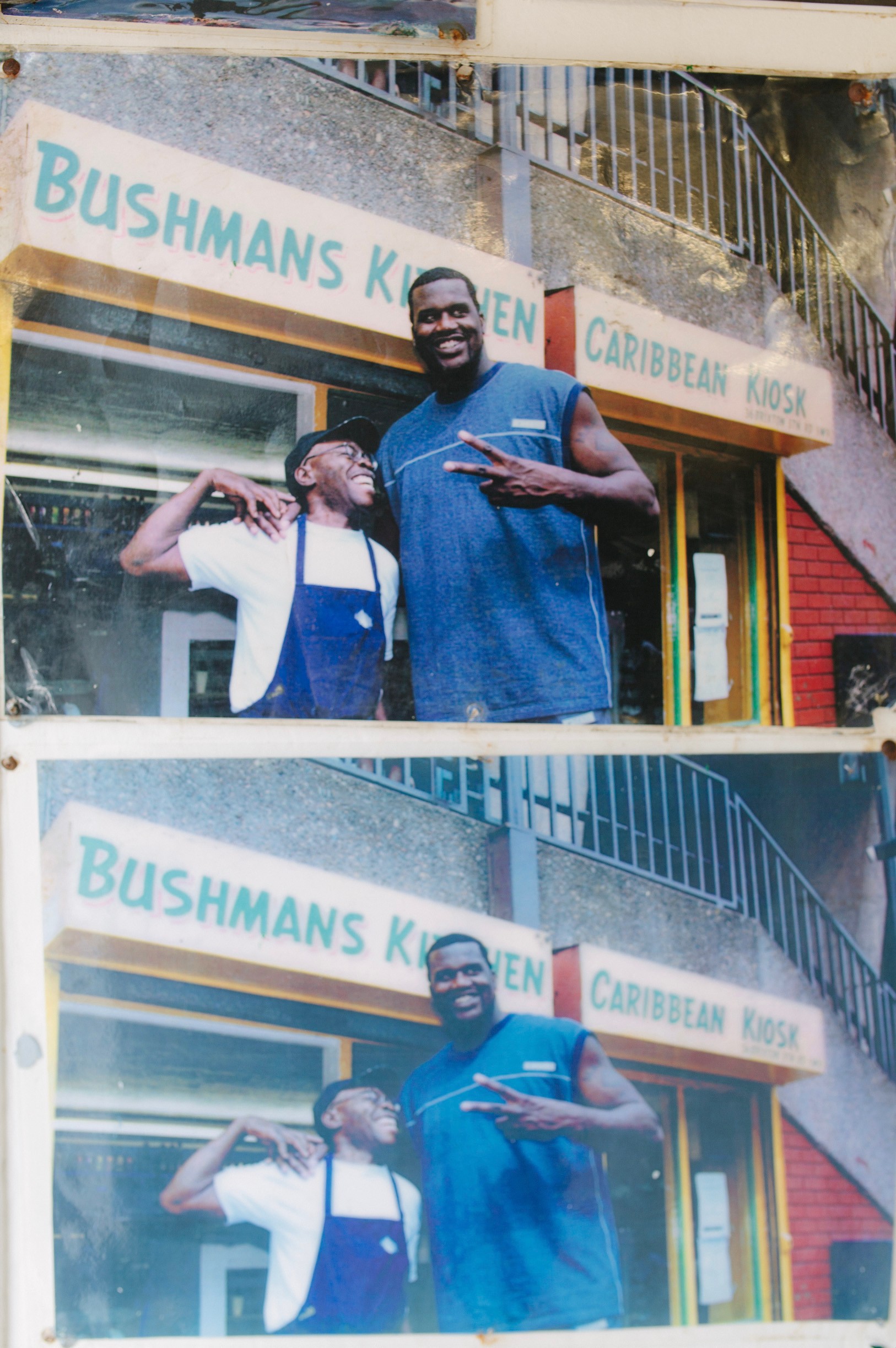

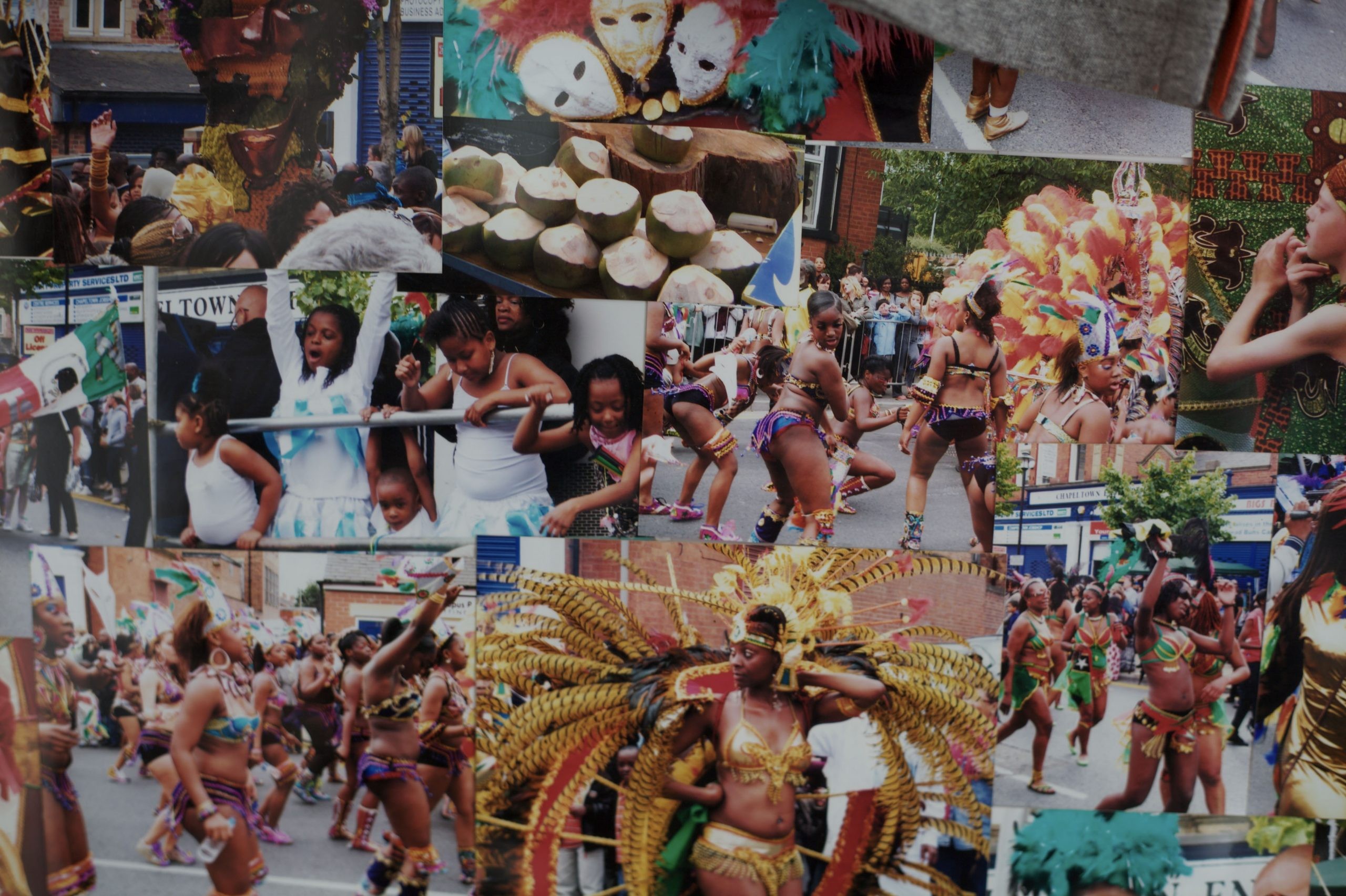

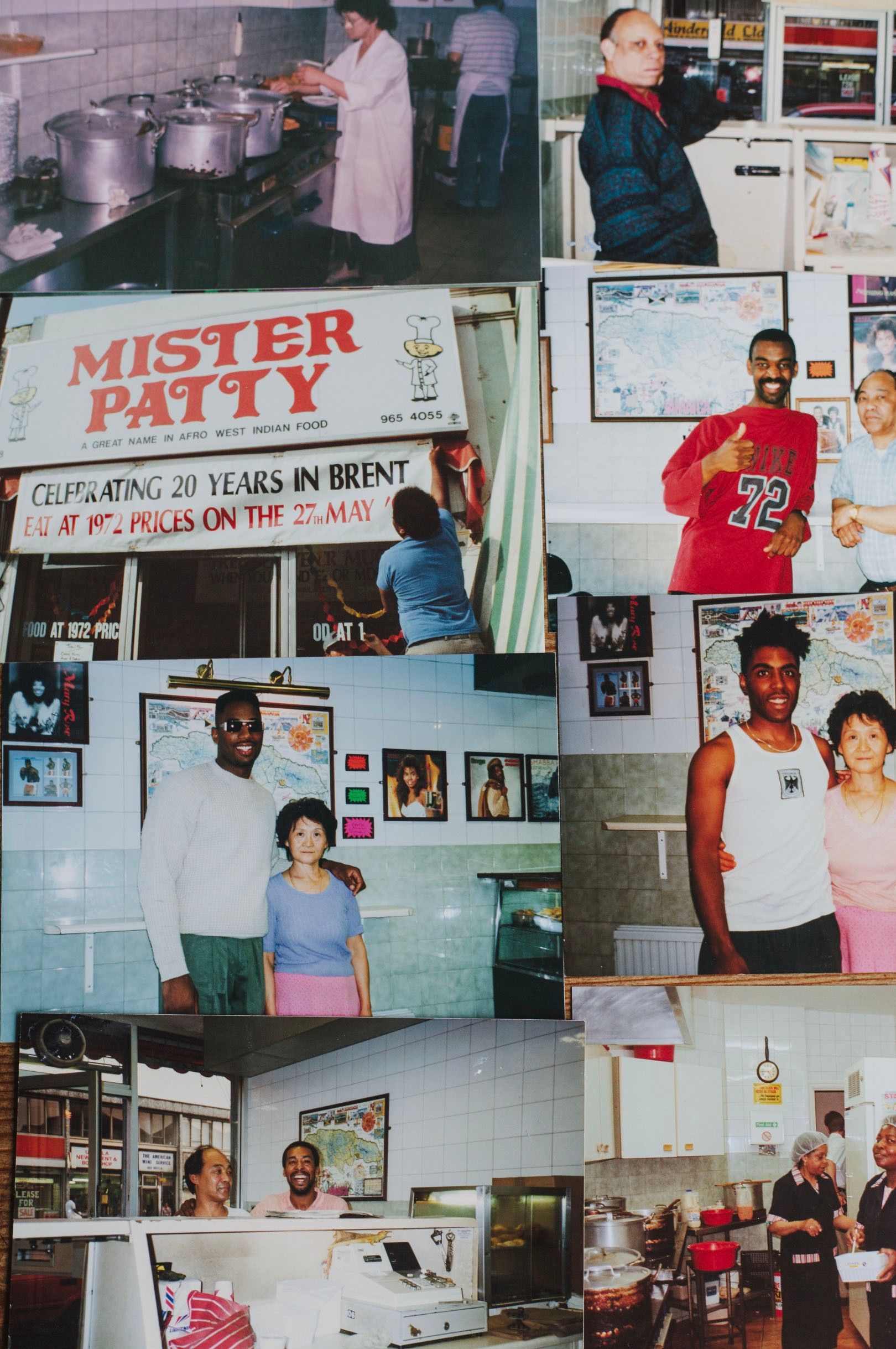

Over the past year, Riaz Phillips has been travelling up and down the UK meeting and eating his way through the world of Caribbean cuisine, finding out what food means to those who brought it with them over the Atlantic. We had a chat to him about the project, as he works to raise the funds to publish the the book. Skin Deep: Tell us about your book Belly Full and how you came to put it together. Riaz Phillips: All my grandparents are from the Caribbean, and some time after my grandmother Mavis passed away last year I realised I’d never really asked her many questions about her experiences coming over to England. I vividly recall how important food was in our house and whenever I came in, or there was “company” over, food was being made. Whatever the meal, I remember she always did yam. And I always ate it but I never asked where it came from or why for over 20 years she always made the same foods. Caribbean food places across London have been growing more popular since my childhood, and as someone who had been going to them since I was a child, I had always wondered who the people behind them were. When you’re a kid you don’t really consider that there are people and families behind these places just like your own. So I set about going to Caribbean takeaways across London, just showing up and asking if I could talk to the owner or chef about their experiences coming over to England and why it was important for them to continue on with Caribbean food and culture. The more I spoke to them, the more they mentioned the dwindling presence of their culture on the high street – places like cafes, butchers and bakeries – so I ventured out to visit and document these places. I’ve also been into photography for a long time, so naturally I took pictures of everywhere I was going. As I did more general research about African and Caribbean experiences in Britain, and learned more about the stream of racially-charged riots that took place over the years, I began to read more about places like Chapeltown in Leeds, Lozells in Birmingham, Moss Side in Manchester and Toxteth in Liverpool. I made a point to visit all of those places and more, even if it was a five-hour national express coach ride. SD: You’ve spoken about the relationship between food, culture, community and history. Why do you feel it’s important to make and maintain these connections? RP: Whenever a culture is displaced en masse and finds home in a new place, one of the first public spaces in which people often revive their culture – first for themselves and then for a wider audience – are restaurants, through food. Naturally, as people need to eat everyday, a lot of these places become communal, spaces where people can connect with others from their background and culture. With this in mind, even if it’s just things like a vinyl record, a detailed map or a National Hero poster hanging up on the wall inside, I think that these relics become very important over time as people in a new country grow further detached from their previous settings. For me, I find that it helps to keep something of a connection to the place where my parents and ancestors are from. I feel this is even more important for grandchildren and great-grandchildren who are usually assimilated into the culture of the country they are born in. SD: Can you share some anecdotes, stories of people you met, or interactions you particularly enjoyed whilst making the book? RP: It took over a year to organise all the meetings and to write up all the profiles, because as you can imagine every place I went to had a story. Roaming around up north was always interesting. I hate to say it, but people really are friendlier up north! The amount of times I was given lifts or invited into people’s homes was mind-blowing. When I phoned the owner of South London’s famous “Cummin’ Up” – Richard Simpson – who I’d never met, he said that he had a tiny bit of time to chat but if I travelled with him to his other store in Brighton that same day it might be better. I didn’t have any plans so a few hours later there we were driving to Brighton – jamming with him and the manager who had the thickest Jamaican accent I’d heard in a long time. It was one of those random things that turns out to be amazing. He knows everybody who’s everybody in the Caribbean food world and has helped a lot with this project. SD: Why do you think publishers felt that Belly Full was too niche to fund? RP: To be honest, I probably went about it in completely wrong way. Some of these places probably get hundreds of emails a day saying “publish me”. There is also the added element that Caribbean food itself is still niche in Britain compared to the likes of Asian food, so it makes sense that any book covering the topic would be niche too. SD: Who did you make the book for and how are you hoping that they’ll react to it? RP: The book is split up into over 60 profiles. I tried to write it in a way that would be interesting for people familiar with Afro-Caribbean culture and history in Britain. I tried to do as much digging and research as possible to make sure that it would both be revelatory and introduce them to new information. The hope is that the book will function as a sort of guide for people who have always been curious about the happenings and, of course, the food inside these places in their own neighbourhoods that they may have walked past many times. SD: Can you tell us more about your publishing company, Tezeta Press (a protest against forgetting)? RP: I kept coming across the phrase ‘A protest against forgetting’ from reading two massive collections of interviews by art curator Has Ulricht Obrist called Interviews: Volume 1 and Volume 2. Every interview was amazing and I just happened to read them at a time when I was starting to develop ideas about a starting a blog, website or publishing company. Whether it was writing about food or music, I’ve always known that I wanted to tell stories and broach topics that I found were under-represented or “forgotten”. SD: Are you planning any future projects? RP: Food is a popular topic and a great gateway into other subjects. So I’d be interested to pursue more explorations into different African and Caribbean cuisines for sure. I’m very interested in the direction and diversion that African food took when slaves, migrants and travellers reached different parts of the world and how those cuisines interacted with the different cultures and foods of those places. At the moment, I’m specifically interested in Brazil, which until a few years ago I hadn’t realized had the largest slave count and subsequently the largest African and Black population outside of Africa. SD: What’s your favourite Afro-Caribbean dish? RP: I’m Jamaican, so it’s sacrilegious, but I love anything with Roti (which is more Indo-Caribbean). My mum has been buying Roti from Horizon Bakery since I can remember. Anything inside it tastes amazing: jerk chicken, curry goat, saltfish and ackee, doesn’t matter. Sweet cornmeal festival dumplings and chickpea doubles hold me down for a quick snack too. Riaz has a few weeks left to to raise enough funds to publish his book. Check out his Kickstarter campaign to support the project.

Skin Deep meets Belly Full

Over the past year, Riaz Phillips has been travelling up and down the UK meeting and eating his way through the world of Caribbean cuisine, finding out what food means to those who brought it with them over the Atlantic