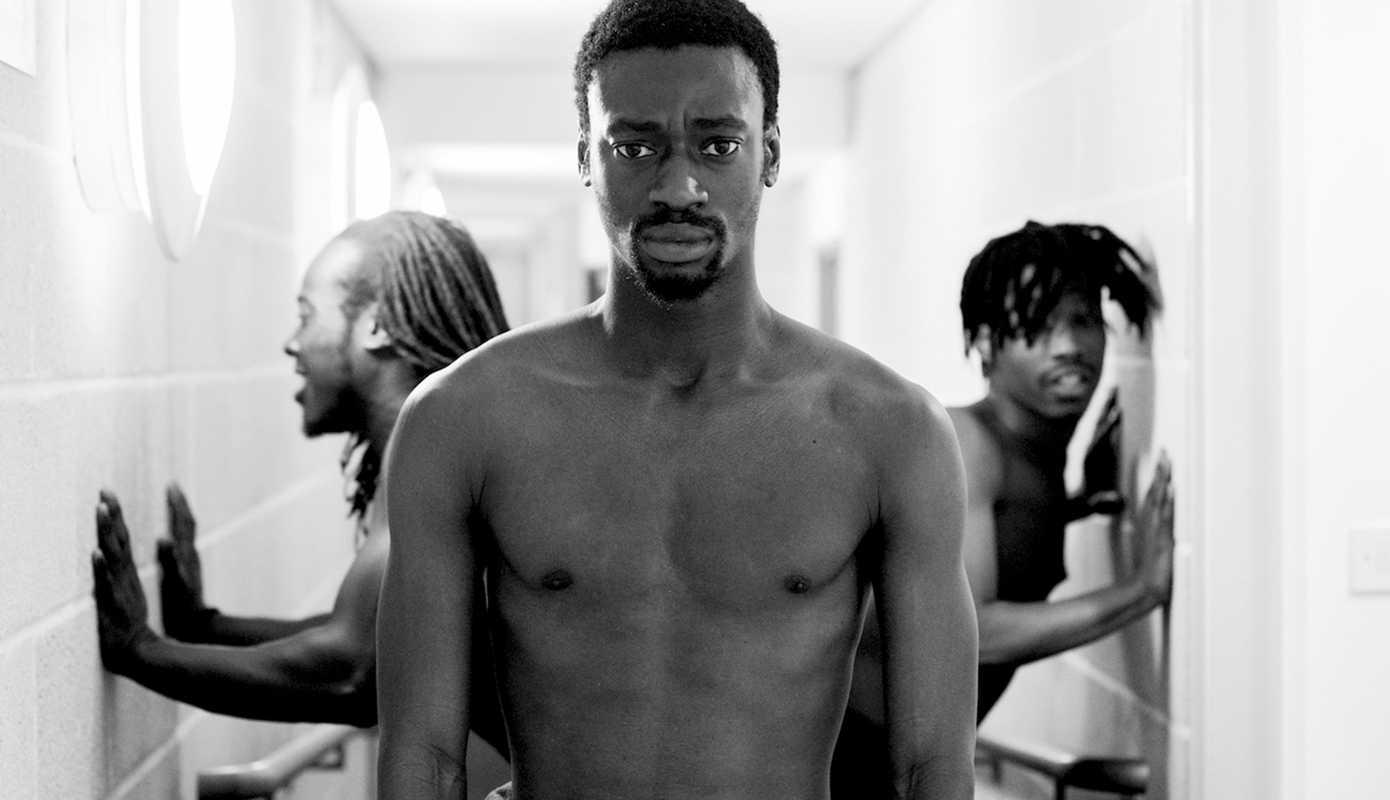

Nominating Kwame Asafo-Adjei for the Arts Foundation Futures award, Robert Hylton interviews the now winner on cultural identity, dance and the influences he draws from.

Robert Hylton: How did you get into hip hop dance?

Kwame Asafo-Adjei: I started about ten years ago, dancing with Stefan Sinclair and his crew, Innovate, in Elephant and Castle. Then moved to a crew called Unity where I learnt more choreography and started to understand how to pick it up faster. Influenced by Michael Jackson, I got into locking, popping and gliding. From the beginning, I chose to move towards hip hop theatre because I wanted to be realistic. I wanted to work with a format that allowed me to be political. I wanted to create change in society and didn’t feel like the commercial world would enable that.

RH: Did you get involved with any commercial ventures?

KAA: At one point Unity was changing and joined ‘Got To Dance’, the Sky One competition, but I wasn’t chosen to do it. Leaving Unity was a mutual decision. For me, working on the commercial side of street dance meant losing control and identity.

RH: But the format can be played to your advantage, for example, Diversity did very well.

KAA: Yes, and also Flawless.

RH: How does your background and hip hop identity work for you?

KAA: I was born in Scotland, lived in London and my family are from Ghana. I lived and studied in Queensland, Ghana for two years when I was sent there for being a bad child. In Ghana, which has a very rich culture, I learnt discipline and the appreciation of the essential things, like water and light, butalso, learning how to be assertive, unafraid and to aim for what I want in life. So, Spoken Movement, my company, is me. One of my pieces, Family Honour, was inspired by my family in Ghana. I learnt traditional Ashanti dances in Ghana which they call ‘Adowa’ meaning ‘every action has a meaning’ and this was very liberating for me.

RH: How old were you when you returned to the UK?

KAA: 14. I shared a fold-up Nokia 33/10 with my sister! This symbolised the UK for me, the ability to open and close. Africans are very upfront and honest but in the UK it’s a chess game. In the UK you must choose your words carefully.

R: Are your influences Ghanaian or are they British?

KAA: They’re both! My family is from Ghana, we don’t speak English, we speak Twi. But I am also a black guy from South London and that’s the truth. On a daily basis, when I’m wearing a black hoodie, I’m getting stopped. It’s normal. When I’m stopped by the feds, I laugh. They’ll ask, ‘why are you laughing?’ And I say because I knew I’d be stopped. And then they move on. It’s sad, I’m accepted and then I am not but all of this influences my work. I wrote a piece called ‘Chi’ about south London society and it opens up the conversation that will then hopefully implement change.

RH: This relates to ‘double consciousness’. The real self and the African self that is managed by the country you are in.

KAA: If I couldn’t speak honestly, I wanted to communicate through my work and produce a guttural response. The truth is the truth. Spoken Movement is my outlet.

RH: How do you express the tension and release themes in your work? Why popping and not Krump?

KAA: I’ve gotten into Krump more recently. I started with popping when Shawn Aimey from Plague and Stefan Sinclair taught me it. As well as being aesthetically amazing, popping has an ugliness. But there’s beauty in that ugliness. It’s in the darkest tunnels where you’re going to find the most light. In hip hop theatre where I try to blend the form – the pioneers may not like this though. For me, there’s a frequency and physicality, so Krump is more external but popping is internal. My emotion and my personal life are in my work, and popping is a form that allows me to take control of my work.

RH: How political is your work?

KAA: I’m a reporter and I have to report the news otherwise how are these kids going to know about what’s going on? If people don’t report the news and create reference points, their culture and history will be lost. The perfect example is when Missy Elliot resurfaced, millennials didn’t know who she was and that was crazy to me! Nobody knew who this artist, this woman, who had had such a huge impact on the culture… the Missy Elliott!

RH: Yes, but some are rejecting the ‘microwave’ experience. That is why recognition of the arts is so important, to encourage and nurture the process and those that are going through it.

KAA: And I agree, but everything I see is based on my experience. Some people are here for the journey but I do feel there needs to be more focus. I ask myself why I got involved and it’s about the voice; creating awareness and speaking the truth. It was always about the love and not the commercial aspect of dance. Everything is hype before it becomes solid. I am always trying to understand my environment.

RH: Can you tell us about Obibini which deals with cultural identity? Why do you think it was so well received by the public?

KAA: It was about the evolution of black culture and how it stands in modern society. The reason why I called it Obibini is because it’s a Twi word meaning ‘black person’; identifying ethnicity. I wanted to create stereotypes for people to analyse and reflect on. I didn’t want to create a ‘show’, I wanted to create an experience that people can take away with them. Using the thread of white supremacy, I wanted to show the evolution of this, to ask who actually created this piece of work.

RH: Your critical thinking is integral to your work. The symbols and the fractured identity we carry. Being a reporter allows you to focus on that identity, reforming and making whole again. You are focusing on being part of the healing process.

KAA: The purpose of Obibini was to encourage the whole of society to reflect and consider where they stand and whether it’s positive or negative. Are we conscious of ourselves or not? I wanted more than anything for people to feel and dissect these issues. It was also certainly a semi-autobiographical piece.

RH: If you won the Arts Foundation Fellowship what would you use it for?

KAA: I would gather and create resources to enable change. I would buy a sewing machine and a laptop. I would use the money to cut out the middleman! I would invest in the development of my artists and my company. I would like to be an example of change.