I have this skill, which for many west Africans isn’t a skill at all, and it is that I can almost always tell if someone is Nigerian from their first hello. I’m best at discerning Igbos and then Yorubas, and sometimes, although not as often, Hausas. I can even recognise those native to the Rivers and Delta regions, and it never really takes more than a few sentences. Last month, when a friend and I got an Uber in Amsterdam, I knew the driver was a Yoruba man before I read the ‘Ade’ on his license. Maybe it was the scar on his cheek, or the discreet way he raised his eyebrows, or that he saw my friend’s Sierra Leonean name in his app and waited longer than he needed for us to find his car.

Whatever it is that has us recognising each other on sight, it in turn triggers an involuntary scrabble for connection, much of which occurs in my head. If my Uber driver is a continental Nigerian, I cannot help but trace their imaginary journey to the city we are in and the car ride we are sharing. I will almost certainly wonder what their childhood town looked like, I will think about how many kids they do or don’t have and where those kids live, how many degrees they aren’t using, how often they give themselves the time to think about the meaning of home. Our stories are multiple in the diaspora, and ride sharing apps have, for me, become a peculiar stimulus for dredging up the rootless nostalgia they foster.

‘On Loneliness,’ Fatimah Asghar’s essay in The Good Immigrant USA, builds out of an Uber ride with a Pakistani driver in her new home, Los Angeles. The essay, a lyrical exploration of the emotion, finds threads between Asghar, the driver, and their histories – overlapping and not – to contend with the isolation gripping her as she grows accustomed to the city. It is as beautiful as it is familiar, and it gave me the space to think about the contours shaping my own diasporic journey.

“Loneliness is an emotion that we all try to shy away from because we don’t want to feel things we consider negative,” Asghar commented. “I actually think loneliness can be really productive because it’s just pointing you to the moments of being able to access the specificity of you. It’s pointing you to something that is within you that you haven’t quite wrestled with.”

For Asghar, diasporic loneliness is distinct, it’s “feeling like a fraud, and feeling like you’re not always enough.” It is an ever-present vibration under the skin, in some moments unremarkable and in others turbulent, prompting the weaving of narratives about cab-driving strangers out of temporal and artificial threads. No loneliness penetrates quite as deep as that born from a fragmented sense of home and self. When Asghar was approached by Good Immigrant co-editor Nikesh Shukla, she took the opportunity to scratch the surface of its specificity, to speak to “those real, real moments of feeling like an approximation your people. A bastardization of your people. I think that that’s a really interesting terrain to live in.”

That terrain is marked by consistent yearning for a shared geography and cultural experience that is at once harmonious, inclusive and complete. It is a yearning for a place that largely exists in the imagination, particularly for those of us with intersecting identities regularly erased from our cultural origins, who rarely travel ‘home,’ or for whom that home technically no longer exists. Acknowledging the ways diasporic loneliness can easily seep into our everyday, I ask Asghar how and where she finds home.

“I think I’m always trying to figure that out,” she responds.” I think it’s a feeling. It’s the feeling I get when I am at peace in the iteration of the body that I’m in.”

For Asghar that feeling is sometimes found in the people who’ve made it possible for her to be alive, sometimes in the little cocoons of experience that remind her of her childhood, but ultimately, home is inherently fragmented and always something to work toward. “I’m always trying to find home,” she says, “and I don’t know if I ever will.”

It can feel painful and difficult to have the place in which you seek solace be ever-shifting. I’ve come to learn that the home I find in one particular space, person, or thing may not exist in another, and so the kind of rest I am able to find at any given time, and by extension how I move through the world at any given time, will always be contingent on this sense of fracture, which sometimes feels like loss. But it can also feel honest and beautiful, knowing that the me I come back to at the end of each day is always in conversation with the space I am in. It can bolster the grasp I have on my sense of self, allowing me to have a more conscious understanding of my existence over time. It can be liberating, and powerful in fact, to lean into the multiplicity that results from an unfixed centre, and I think this is part of why I have long been drawn to the flexibility of Asghar’s writing, because it reminds me that our creations can be as multiple and responsive as we are.

“I think genre is a myth, you know?” Asghar says to me. “If you’re a writer, there’s so much you can craft. There’s such a city of language and syntax, and so much of writing is just different components of that.”

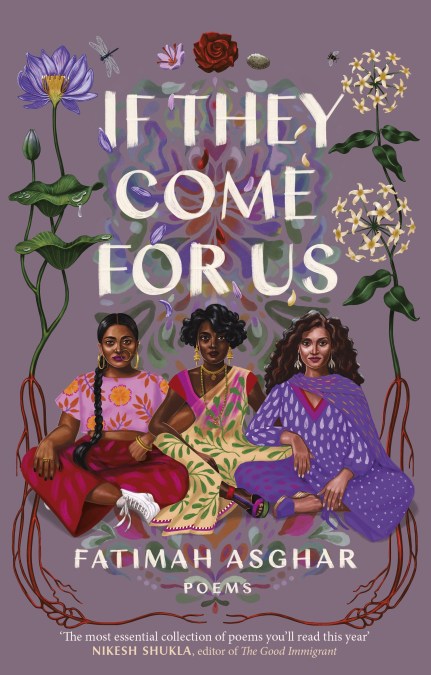

I first came across Asghar’s work in 2017. Snuggled up in my tiny Brooklyn bedroom, I watched every episode of her web series Brown Girls, co-created with Sam Bailey. Brown Girls felt familiar in its pace. Slow without losing its vibrancy, Asghar and Bailey managed to accurately channel the impossible urgency of millenial life. The series is now being developed at HBO, and marks just one of the writer’s many ongoing projects, each doing their own distinct but necessary work. The aforementioned essay ‘On Loneliness’ makes a melody out of the mundane, breaking open the ways we imagine ourselves and each other in our everyday, and her latest solo offering, the poetry collection If They Come For Us, is itself an epic, potent in its brevity and visual currency. For me, Asghar’s work has become another home, an active space where I can drop my shoulders half an inch and have what is often unspoken about being black, brown, femme and of multiple spaces acknowledged and lifted up. I wonder if impact is ever a guiding factor in Asghar’s creative process?

“When I’m writing a thing, I don’t necessarily think about the work that it will do,” she responds, “because a huge part of my writing process, in any genre, is about getting to a pretty vulnerable place with myself. And it’s weird, because I also have the deep idea of everything I make belonging to and existing in community.”

An increasing number of people across the globe are finding home in Asghar’s work, establishing her place in the growing set of important contemporary artists exploring diaspora and its many tangents. Asghar recognises the gravity of this position, as well as the peculiarities of being hypervisible.

“The kind of intimacies that are created can be interesting to navigate,” she tells me. “Sometimes they’re destabilizing because they’re not always reciprocal… you know my deepest ideas, fears and insecurities. But what I think is beautiful is that [the work] acts like honey. I may feel really lonely, and I put out a sprinkle of my work, then people who are like me find me, and now there are more people who are linked to me because they also feel this way.’”

Asghar often thinks of relationship, the balance between engaging with people in the world and working in isolation, as a medium inherent to her artistic practice. And while she may not actively consider the impact of her work as she’s creating it, the importance she places on connection, on existing in tandem with many others who see and understand her, cannot be understated. Asghar’s parents died when she was still very young, and part of the effect of that early experience of mortality, the literal and psychological rupture it rendered, was to crystallize some of the more abstract feelings of diaspora:

“Things like the actual instability of home: what does it mean when you’re an orphan and you’re just being passed around, you know? There’s so much of my life that was in the shadow of death. It was a kind of dual diaspora – the diaspora of my people but then a diaspora of my severing from my family because of my orphaning.”

It is unsurprising to me that Asghar’s work is, in its essence, about home and connection, about how we find ourselves in and with each other. Through her art, and the people it has brought into her life, Asghar is building the foundations she needed for herself, for the young girl who “had these wells of shame” around her orphaning, who was “concerned with if I was like everyone else.” When I ask about her chosen family, the people who function as a strong foundation for her, the joy in her voice is evident.

“I really love my community. I came up in spoken word where we would write together, so there was always a space of sharing and connecting to each other. Then I found several different artist communities and friendships that I feel are so beautiful because they really push me to be better.”

Asghar knows whose opinions she cares about. Her communities, particularly individuals with whom relationships have been built over many years, make her more honest. “You can just be like ‘hey, you’re on your bullshit,” she says, laughing. “When you’ve been reading someone’s work for ten years, it’s like ‘you can trick the rest of the world but you can’t trick me!’”

This raw kind of honesty seems natural for Asghar, in her relationships, in her writing, in her understanding of her own existence and mortality and place in the diaspora. I have a lot of discomfort around death, around loss and change and the idea that we are living through iterations of existence, culture, life, and inextricable relationships, that we will never see or experience again. To be okay with the finite nature of all things, even as time continues on into infinity, feels almost radical. It is saying you are okay with the idea of constant search. The people and places we love, the markers that make us who we are, will be lost and found and lost again and we will continue through the beauty and pain of all of that… until we don’t.

“People joke that I am a pretty morbid person,” Asghar laughs, “and it’s true! I have this little app on my phone that reminds me that I am going to die 5 times a day and…”

Oh my god, I respond, cutting her off.

“[laughter] Death is natural, so why do we have such unnatural relationships with it? Why do we not talk openly about it? Why do we not grieve well? Why do we not have these kinds of conversations that are so inherently important to us as a people and as a species?”

Asghar’s work exists now, in this moment, and that is enough. But it will also exist beyond her, beyond now, doing the work of further complicating the versions of ourselves that we’ve been allowed to see, and letting us feel a little less lost, a little less lonely along the way. I ask Asghar what she would have told her 10 year old self, the young girl who was feeling lost and loss, feeling rupture and a need for somewhere stable to connect to.

“I think I would’ve told her to just lean into what makes you you. There is only one you and you have a relationship with you the rest of your life so take care of that relationship. That relationship is worthy of tenderness and care; I wish I had known that earlier.”

You can buy a copy of Fatimah Asghar’s poetry collection If They Come For Us here, and The Good Immigrant USA here.