This article was made possible by donations to the Black Creatives Fund. Donate now.

I’ve taken bucket baths for as long as I can remember. Sitting criss-cross applesauce in the kitchen sink, as my Mommy gently poured cups of warm water over my luscious baby curls. She would viciously scrub my skin to remove any remnants of the Cerelac that I’d dove face first into, as I winced and sheepishly grinned, more interested in the toy ship that I had brought into the sink with me.

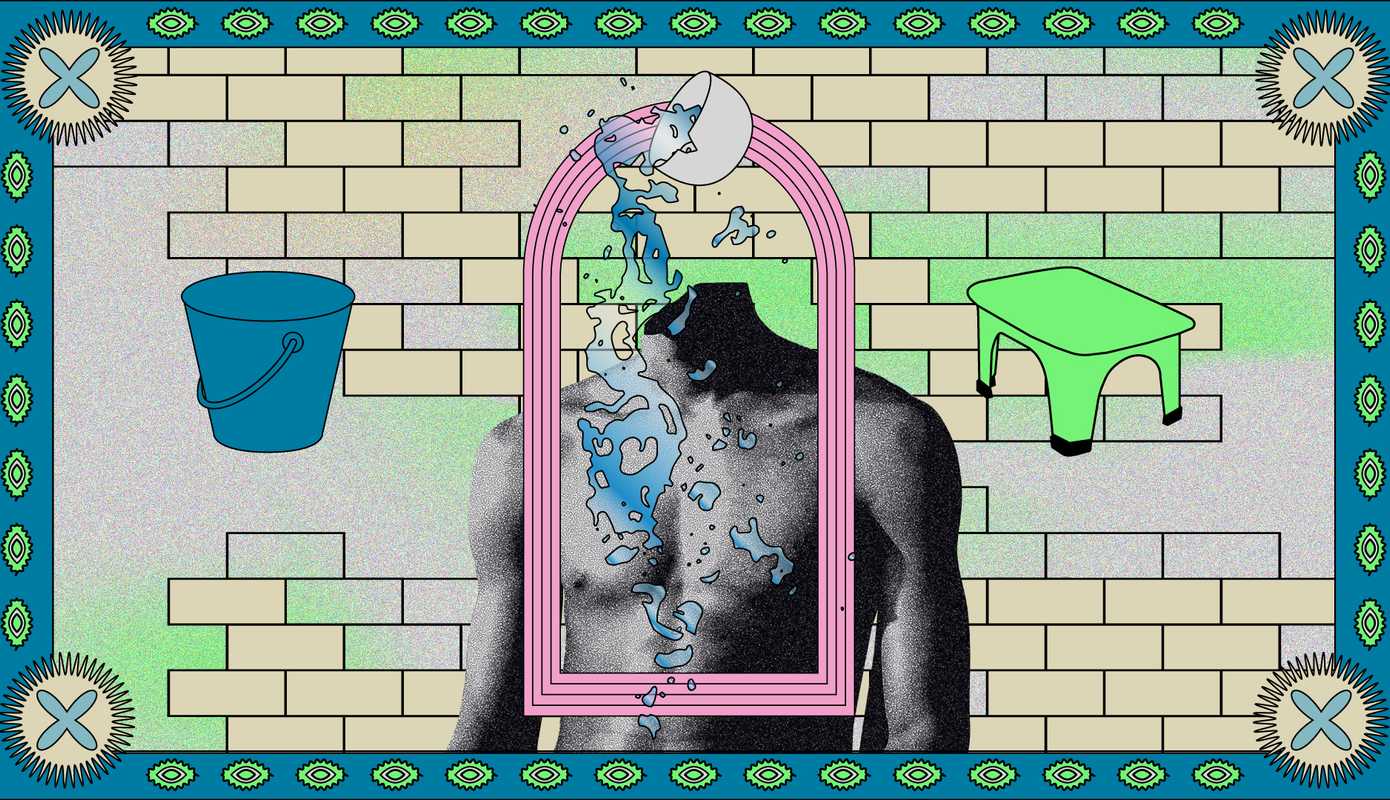

Bucket baths have always been a meditation of sorts. Not as passive as a shower or a conventional bath. In a bucket bath, I am an active participant. Standing in the tub, I scoop water out of the basin and gently tip the cup so the water streams down every crevice, nook and cranny of my body. I feel in control.

I always thought bucket baths were exclusive to those of us who grew up in the Global South, but the movie Moonlight taught me otherwise. I was captivated and surprised by the scene where Little boils a saucepan of water to fill up a bucket. I’d done the same exact thing countless times. It was the first time in my life I’d seen this ritual in a movie. Seeing a little Black boy so much like myself, have a meditative bucket bath in a world where so much was out of his control was liberating. Little was in control.

To journalist Gene Demby, bucket baths represent a reminder of the poverty his family experienced during his childhood and how far he’d come since then. He says in conversation with Moonlight director Barry Jenkins, “My girlfriend always complains that I take long showers because I couldn’t take them growing up.” Referring to the scene of Little’s bucket bath, Jenkins responds: “For that scene more than any other in the film, I’ve had people come up to me who I didn’t expect and say ‘I can relate to that’… anyone who grew up in a kind of hard way where you had to rub two sticks together, they kinda know what that is.”

Anyone who grew up in a kind of hard way understands the ingenuity required to reclaim control in a world that has wrested so much from us. There are clear parallels between me growing up taking bucket baths in the Global South, due to societal norms and inequities of water and electricity supply, and Gene Demby, Barry Jenkins and Little growing up in inner cities in the Global North, also dealing with service delivery inequities in Black communities.

The first time I couldn’t take a bucket bath, I had lost control. On February 16th 2001, at nine years old, I had my first stroke. The next few months were a blur of deteriorating health, excruciatingly traumatizing experimental medical procedures, and doctors telling my parents that I wouldn’t make it to 2002. The entire right side of my body gradually became paralyzed, and I developed a host of other long-term health complications. My mother had to give me bucket baths once again. I could not bathe myself, I couldn’t even passively stand under the shower anymore.

My mother never understood why I made the switch to showers. When my father’s job relocated us to an apartment with hot shower access, I chose ease over effort. Showering was relatively mundane, I had the able-bodied privilege to passively move through the motions. My mother never made the switch to showers. She takes two bucket baths a day regardless of where she is. She’s done so for as long as she can remember – it’s where she feels most comfortable. When my mother had to return to giving me bucket baths in 2001, having bathed independently since I was old enough to, I started to resent them. Still, I was grateful for my mother’s attentiveness, care and lack of awkwardness.

Bathing is a privilege I do not take lightly or for granted as my body often violently shuts down due to the exertion required by a simple bath. I vividly remember this happening one morning in October 2017. I was 25 years old, had survived two more strokes in 2014, yet with time and the help of countless health professionals, I had found ways to manage. I was pushing my body hard through my first ever book tour, spanning 43 cities and five countries in North America and East Africa. Lying in bed at my AirBnB in Vancouver, the day after a successful show, I took my time getting up and heading to the shower. Grateful for the ability to passively stand under the water: feeling it cascading down every crevice, nook and cranny of my body. I felt deeply grateful.

Then everything started to get fuzzy. This fuzzy feeling is often the aura of an impending seizure, so I quickly yanked the faucet shut, gingerly stepped out onto the chalky linoleum floor and extended my quivering left hand to grasp the towel rack. As soon as my hand clenched, the seizure took control.

One hour later, it subsided. I was panting, my naked body shivering and heaving against the frigid linoleum floor. I took stock of my surroundings, squinting in an attempt to focus my facial spasms. The towel rack, viciously torn off the wall, lay mangled across my peppercorn chest hair. I wondered how much this was going to rack up in charges. Being disabled ain’t cheap. I tried to stand up but my legs were paralyzed.

Bathing is a relatively mundane activity to most able-bodied folk. It is a very different experience for disabled bodies like mine. I was able-bodied for the first nine years of my life and I remember enjoying bathing. Taking a bath is one of the few intimate and private moments we get in a day. It’s a moment where we gaze upon our nakedness; some of us revel, others recoil. Bathing is often painful, exhausting and inaccessible for disabled bodies. It serves as a reminder that we live in an able-bodied world where so much is outside of our control.

It’s 2020 and I’m 28 years old now. I have survived three strokes. Bathing in any form is impossible on difficult days because the exertion raises my pain and fatigue levels to a point where my body shuts down. Bathing can also be seizure-inducing, so I can only afford to bathe on my very best health days. In January of this year, I moved back to my mother’s house in Mutundwe, a leafy suburb of Kampala, Uganda. I share my mother’s house with nine humans, five chickens, five dogs and one turkey (RIP sekokko). In my mother’s home, we exclusively take bucket baths. Difficult days are the norm in 2020, due to deteriorating health and inaccessible care services because of COVID. Bathing in any form is impossible on difficult days.

The first accessible bucket bath I took was this year, a month after moving to my mother’s home. It had been four days since I was last able to bathe. I reeked. Changing clothes only did so much for the pungent scent that emanated from my pores. I wanted to take a bucket bath because I stank, but if I stood for longer than a few seconds, my legs would start to tremble and would eventually give out from under me. My mother and Victor, my brother, found me sitting in the bathtub scratching the nape of my neck.

“Are you ok?” they asked.

“I want to take a bath but I can’t stand for longer than a few seconds.”

“I can bathe you,” my mom suggested, but I cut her off. “I’m trying to cling on to the last vestiges of independence Mommy, please. Isn’t there a way that we can make bucket baths accessible, so I don’t have to stand?”

“Give me a minute.” My brother Victor left the bathroom, quickly moving into action. I heard him rummaging around in the adjacent store room. He emerged with a hot pink non-slip grip mat, a fluorescent green plastic stool and a cerulean blue basin. Victor placed the grip mat on the bathtub floor, the stool in the center and the basin at the head. Dropping the chipped off-white plastic cup into the basin, Victor helped me into the tub to test it out. I warily stepped into the bathtub and gingerly lowered my bum onto the stool. Rocking my body back and forth to test the sturdiness, I mimed the action of reaching down to the basin and splashing the water from the cup onto my body. It worked.

Bucket baths represent poverty to some, and comfort to others still. To me, they are a way of reclaiming control. I’m not able to take bucket baths as often as I would like to due to volatile health, but they serve as a refreshing reminder. A reminder that even though I inhabit an incredibly volatile body, that was not built to thrive in this white supremacist, ableist, cis-hetero normative (etc) world, continuing to survive is an act of resistance.

It’s November of 2020 as I write this. I have been using the accessible DIY bucket bath that my brother and mother created for me for nine months now. Bucket baths continue to be a meditation of sorts. Not as passive as a shower or a conventional bath. In a bucket bath, I am an active participant. Sitting in the tub, I scoop water out of the basin and gently tip the cup so the water streams down every crevice, nook and cranny of my body. I feel in control.