In the second week of January 2016 we travelled to the Calais refugee camp commonly known as ‘The Jungle.’ The Skin Deep team had been planning to go, frustrated with the fickle media’s dehumanizing rhetoric and disturbing appetite for flashes of physical violence, and at very short notice we managed to hitch a ride with another group working on a creative project called ‘Refugee Song’. As we drove down to Dover, getting to know our companions and testing our recording equipment, we tried to untangle why we were really making this trip. Two questions seemed to stand out: 1) Are there ways in which you can critique the current handling of the situation by media and governments without retreating to a state of inertia? We have become increasingly uneasy at the paralysis of the Left, who are deeply self-conscious of indulging a ‘saviour complex’ and find it easier to join the stream of critique rather than taking action, for fear of waking up regretful next to another Kony 2012 campaign. Our aim was to offer a reflexive analysis of our experience in an attempt to share practical knowledge and advice, both to dispel dangerous myths and enable people to help. To clarify, by ‘help’ we mean constructive action, action that aids refugees whilst remaining aware of the shared struggle between those people of colour wishing to join the community of Europeans and those who, on paper at least, already form part of it. 2) Can we give an account that challenges and provides an alternative to the largely voyeuristic and dehumanising coverage we tend to receive in the UK? The media’s response to what is happening in Calais suffers from an impoverished verbal and visual vocabulary. Coverage fails to convey the complexity of the lived experience of individuals and communities in the camp, and we are conscious of the manner in which individuals are reduced to sound-bites that support a pre-constructed narrative, the blatant disregard for the right to privacy of individuals in the camp in the pursuit of eye-catching images, and the uncritical perpetuation of the vision of a world divided by borders. These questions must be addressed by a collective such as Skin Deep that aims to be anti-racist, and indeed by our individual selves. As financially secure British citizens of colour, our (dis)connection to/from these people must be explored; what issues are illuminated/overlooked when trying to connect the varied experiences of people of colour through the lens of a post-borders world? We spent only two days in the camp, and stayed at a hotel in Calais overnight. The following reflections on the camp are drawn from this very limited experience; we hope to return over a longer period of time to foster a more nuanced understanding in the near future. This article heads a short series of podcasts and other content on lessons from Calais, and more broadly on the topic of mass migration and its subjects. There is an impossible amount to know about the camp and the people in it, far more than two days will earn you. But for starters, based on our experience, here are five things we think you ought to know about what’s going on in the settlement known as ‘The Jungle.’ What the camp is like The camp is largely composed of tents and wooden structures covered in tarpaulin. Some of the roads are gravelled, others muddy, and the ground is soft and full of bricks – not ideal for tents. There are a limited number of portable toilets, and an even smaller number of shower huts, nowhere near enough to serve the entire camp. It’s fairly quiet during the early hours of the morning, partly due to the fact that it’s so cold at night and most people can’t sleep (temperatures on Monday 18th Jan dropped to below zero). Where people can, they rest during the day. During the time we were there, the volunteers and refugees were trying their best to respond to threats from the French government to bulldoze a large section of the camp closest to the motorway. This appears to be part of a larger plan to eradicate the camp. Roughly 1,500 people had been living in that section; most were from Afghanistan, some from Eritrea, and all had to be relocated. The days were spent moving tents and wooden shelters to other parts of the camp as quickly and calmly as possible. Long hours of labour from both volunteers and refugees meant that almost everyone had been relocated by the time the bulldozers moved in on Monday 18th. We saw a digger being used by volunteers to clear trees to make more room for tents within the limited space left available to them. There are permanent establishments and social spaces such as restaurants, barbers, shops, cafes and places of worship. We ate Afghani and Pakistani food at restaurants that welcomed both refugees and volunteers. In some cases these restaurants were run by individuals who were not actually seeking to cross the border, but had come to Calais from elsewhere in Europe to find work. One restaurant was even jazzed up with balloons and a stuffed tiger. These communal spaces seemed to offer a short respite from the hardships of daily life in the camp (as well as a place to recharge phones). Whilst watching a Bollywood movie and drinking a sweet chai, there were points when we could even forget where we were – though that may have been easier for us than for those without a UK passport. Contrary to what has been reported, it was clear to us that not every moment in the camp is spent trying to cross the border. The people living in the camp In theory, everybody knows that there are people here. Lots of people. But the reductive language with which those living in the camp are discussed made even the most basic and familiar human interactions we experienced over the two days quietly astounding. The total number of people living in the camp as of January 2016 lies approximately between 6,000 and 7,500. It appeared to us that the camp’s inhabitants were about 90% male, though we recognise the possibility that women and children may be more likely to remain inside their shelters and not visible to us during our visits to the camp. Contrary to what many think, the number of Syrian refugees in the camp is actually fairly low. The majority of people there are from Afghanistan, but there is also a large Sudanese population, as well as people from Eritrea, Ethiopia, Iraq, Syria, Iran and Pakistan. The camp is generally self-organised around nationality/language. We were told by two Eritreans that there is a good relationship between the different communities within the camp, and we can therefore speculate that this demographic division is merely the result of linguistic, cultural and religious practicalities and shared cultural and religious practices. We can also imagine that after so many weeks and months of fear, strangeness and not-knowing, the pull of the familiar would make one gravitate towards the known, the things that might remind you, even just a little bit, of home. We certainly aren’t in a position to testify that tension and violence amongst the refugees doesn’t happen; it is 6,000 young men living in close proximity and under intense pressure, after all. But from our limited time spent in the camp, we saw no evidence of significant tension other than that caused by the intrusion of the French state. At one point, we chatted with a young Afghani man making naan in a tandoor at the door to a restaurant. He had already made the journey to the UK and unsuccessfully applied for asylum twice before. The first time he was sent back to Afghanistan. The second time he was deported to Italy. He told us: ‘I am an asylum seeker, so I will keep claiming asylum until I am granted. What else can I do?’ We asked why he wanted to settle in the UK. He explained that like many other men in the camp, he had a network of people in the UK already – friends and extended family – and that English was the only European language he spoke. Speaking English was common to many in the camp due to the long history of British involvement in their home countries. The Afghan man emphasised to us the importance of learning other languages; he spoke seven or eight, a shameful reminder for us of the UK’s arrogant failure to encourage its citizens to speak or understand the languages of others, and the deep hypocrisy of demanding that migrants learn English. He also reminded us that no matter how many languages we learn to speak, we must never neglect the languages of our mothers and fathers. It’s worth pointing out that of those we spoke to, none chose to make the journey to the UK based on any kind of misplaced fantasy of a British ‘good life’ idyll, a drizzly equivalent of the American Dream. We did not hear anything about ‘unemployment benefits’, and everything seemed to be centred on reconnecting with loved ones and establishing a life of work and fulfilment. Many of those who had left Afghanistan had done so due to the persecution of the Taliban. Those we spoke to from Eritrea had left to escape the toil of a military service that may be extended indefinitely. We did not get the chance to speak to people from Sudan, Iraq, Syria or any other countries, but it is clear from the most basic understanding of the differing political, social and economic climates in these states that there is not just one factor that pushes people to exodus. Their motivations are as complex and distinct as the countries from which they have come. These people are, unsurprisingly, multifaceted. Where aid comes from It appeared to us that aid is made available to the refugees solely through the efforts of the volunteers. Larger aid organisations are conspicuously absent. The impression we received from volunteers was that despite their supposed independence, larger aid agencies have been discouraged by the French government from providing aid, medical assistance and legal advice to the camp, because the provision of these resources has the potential to prolong the camp’s existence, something the French state is trying to avoid (seemingly) at any human cost. There are several smaller initiatives offering assistance, such as the recently opened Legal Centre, run by a young woman called Marianne (who you’ll hear from in the podcast series). The centre offers a space – built by Carpenters Without Borders – where refugees can learn about their rights and the legal processes of seeking asylum. The volunteers we spoke with in one aid warehouse appeared to be largely between the ages of 18 and 35. The slightly older volunteers tended to be in managerial roles, with a few seeming retirees either driving vans or helping in the kitchen. Despite the difference in experience, there remained an air of approachability, with those more seasoned looking out for the health and wellbeing of the new arrivals. The demographic was almost completely white and predominantly English, with a handful of French volunteer groups and other Europeans. We are unsure as to the reason for this. To an outsider, the warehouse full of shoes, clothes, food, cooking utensils, sleeping bags and tents may have seemed chaotic, but during our time there it seemed pretty well-organised, irrespective of the high turnover of volunteers (most are only able to help for a short amount of time). Generally, to our eyes, the help of the volunteers was welcomed by those living in the camp, and good relationships seemed to have formed between refugees and the more long-term volunteers. Again, we cannot say that clashes between camp inhabitants and volunteers do not occur. But when considering the possibility of such clashes, we think it’s important to contextualise the tensions that may fuel them within the broader atmosphere, one rife with anxiety over the future of people’s homes, possessions and physical safety. How the media operate Our time in the camp was repeatedly studded with pangs of unease when we witnessed instances of voyeuristic, insensitive conduct from journalists and photographers. On multiple occasions, we witnessed photos being taken, often covertly, of people who had very explicitly asked to be left alone. Not only does unwanted/unknown filming or photography disregard a person’s right to privacy and autonomy, but photographing the faces of people in the camp can also pose a very real risk to their claim for asylum. Since September 2003, the Dublin II regulation has determined which EU member state bears the responsibility for processing particular asylum claims. Any state deemed to be the asylum seeker’s ‘port of entry’ into the EU is responsible for offering that refugee asylum if the correct criteria are met. This means that evidence tying an asylum seeker to an EU country other than that claimed to be their first point of entry – such as a photograph of someone in Calais – can jeopardise that person’s claim to asylum in a country of their choice – such as the UK. The irresponsible behaviour of media personnel will be discussed further in the podcast series. The intentions and tactics of the French state At the distant edge of the camp we could see a tract of land filled with repurposed white shipping containers, stacked two stories high. This yard was the ‘accommodation facility’ that reportedly cost the French government ‘£20 million’ to construct. Do not be fooled, friends. Alongside the bulldozing and the choking of aid, these containers are another means by which the French state is attempting to eliminate the camp and place those people living in it firmly under its control. Whilst the containers do contain heating and basic washing facilities (but no heated towel rails – sorry Daily Mail), there are many reasons why to date only 140 individuals have agreed to move from the camp into the facilities. There is simply not enough space for all those it is supposedly intended for and, unlike in the camp, there are no communal spaces, places of worship, restaurants or shops. Most importantly, however, is the fact that a hand scan is required to enter the facility. Many of those seeking asylum are concerned that these biometric scans will be used as evidence of an alternate point of entry into the EU (much like unwanted photographic evidence). The French state denies these claims, but it’s clearly and understandably hard for the camp inhabitants to trust the entity that seems to have little regard for their safety or wellbeing. So acute is the fear of harming their chances of entry to the UK that thousands of people endure the freezing cold in mud-soaked battered tents, knowing that warm beds in dry containers are just a few minutes away. When you see the French police in their jet-black body armour, lurking over the underpass that serves as the entrance to the camp, it is easy to think that the responsibility for all of this lies at the feet of the French state. But we should not forget that the UK plays an active part in determining what is and what is not happening in Calais today. Its island status has awarded the UK a unique position with regard to Dublin II. Physically separated from the mainland, the UK has been able to neglect its share of responsibility towards those seeking refuge in Europe, a duty founded on the concept of a common humanity. The UK has instead directed its efforts and resources towards bolstering its border ‘defences’. It must never be forgotten that the UK is directly responsible for the conditions that have provoked many people to leave their countries of origin. Whilst in the camp we read the testimony of a young man from Helmand province in Afghanistan who had served as a translator for the British forces. The compensation offered by the British government for him to ‘hide from the Taliban’ was insufficient; no amount of money could protect this man whilst he remained in Afghanistan. And now he is here, in Calais, and his is not an isolated case. The UK’s colonial impact, which sent shockwaves around the world that reverberate loudly in Calais, will be explored in greater depth in the podcasts to follow.

***

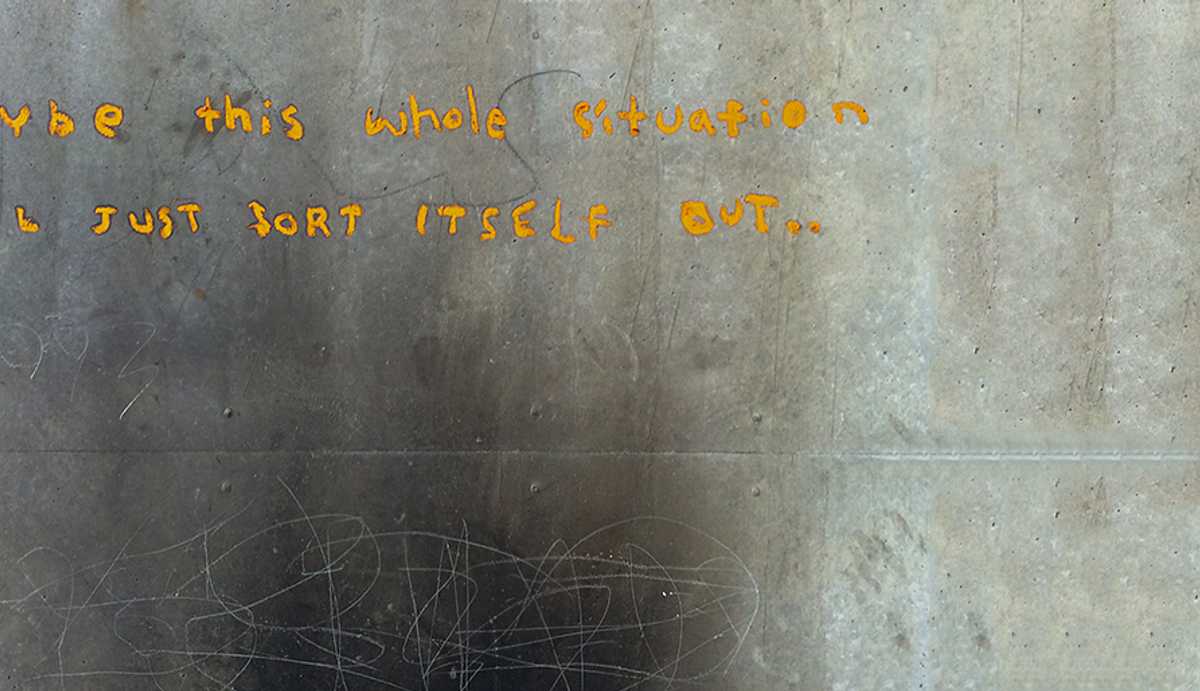

This article and our upcoming podcast series seek to understand and convey in greater depth the distinct culture(s) and scenery that have developed in the occupied spaces that form around borders. We will attempt to situate us ourselves in the context of the mass movement of bodies of colour, and we will examine reflexively the effect and potential problems with our observation of phenomenon and the people caught up in it. Perhaps most importantly, we will contextualise what is going on in Calais, and similar sites of migration and restriction, within a broader European and global landscape, linking the journey of the refugee now to the colonial past and present of the west. If you are interested in volunteering in Calais, please do it right. Here are a few good resources to get you started. General Information Location of Organizing Efforts Calais – People to People Solidarity – Action From UK Volunteer Group to Calais Photographs by Jeremy Whelehan